Militias Shop for Military Arms at Weapons Bazaars on Facebook

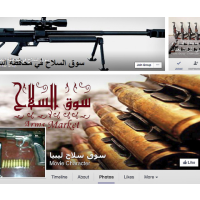

Facebook page featuring Iraqi and Syrian arms markets (photo: Facebook)

Facebook page featuring Iraqi and Syrian arms markets (photo: Facebook)

By C.J. Chivers, New York Times

A terrorist hoping to buy an anti-aircraft weapon in recent years needed to look no further than Facebook, which has been hosting sprawling online arms bazaars, offering weapons ranging from handguns and grenades to heavy machine guns and guided missiles.

The Facebook posts suggest evidence of large-scale efforts to sell military weapons coveted by terrorists and militants. The weapons include many distributed by the United States to security forces and their proxies in the Middle East. These online bazaars, which violate Facebook’s recent ban on the private sales of weapons, have been appearing in regions where the Islamic State has its strongest presence.

This week, after The New York Times provided Facebook with seven examples of suspicious groups, the company shut down six of them.

The findings were based on a study by the private consultancy Armament Research Services, or ARES, about arms trafficking on social media in Libya, along with reporting by The Times on similar trafficking in Syria, Iraq and Yemen.

Many sales are arranged after Facebook users post photographs in closed and secret groups; the posts act roughly like digital classified ads on weapons-specific boards. Among the weapons displayed have been heavy machine guns on mounts that are designed for anti-aircraft roles and that can be bolted to pickup trucks, and more sophisticated and menacing systems, including guided anti-tank missiles and an early generation of shoulder-fired heat-seeking anti-aircraft missiles.

The report documented 97 attempts at unregulated transfers of missiles, heavy machine guns, grenade launchers, rockets and anti-matériel rifles, used to disable military equipment, through several Libyan Facebook groups since September 2014.

Last year ARES said it had documented an offer on Facebook to sell an SA-7 gripstock, the reusable centerpiece of a man-portable anti-aircraft defense system, or MANPADS, a weapon of the Stinger class. Many of these left Libyan state custody in 2011, as depots were raided by rebels and looters.

ARES said it documented Libyan sellers claiming to have two complete SA-7s for sale, two additional missiles and three gripstocks. An old system, SA-7s are a greater threat to helicopters and commercial aircraft than to modern military jets.

Machine guns and missiles form a small fraction of the apparent arms trafficking on Facebook and other social media apps, according to Nic R. Jenzen-Jones, the director of ARES and an author of the report.

Examinations by The Times of Facebook groups in Libya dedicated to arms sales showed that sellers sought customers for a much larger assortment of handguns and infantry weapons. The rifles have predominantly been Kalashnikov assault rifles, which are used by many militants in the region, and many FN FAL rifles, which are common in Libya.

All of these solicitations violate Facebook’s policies, which since January have forbidden the facilitation of private sales of firearms and other weapons, according to Monika Bickert, a former federal prosecutor who is responsible for developing and enforcing the company’s content standards.

The use of social media for arms sales is relatively new to Libya. Until a Western-backed uprising against Moammar Gadhafi in 2011, which ended in his death at the hands of an armed mob, the country had a tightly restricted arms market and limited Internet access.

But social media-based weapons markets in Libya are not unique. Similar markets exist in other countries plagued in recent years by conflict, militant groups and terrorism, including arms-sales Facebook groups in Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

On Monday, The Times shared links for seven such groups with Facebook to check whether they violated the rules. By Tuesday, Facebook had taken down six of the groups. Bickert said that one Facebook group — which displayed photographs of weapons but only discussed them and expressly forbade sales — had survived the company’s scrutiny.

Bickert described the company’s policies as evolutionary, reflecting shifts in its social media ecosystem.

“When Facebook began, there was no way to really engage in commerce on Facebook,” she said. But in the past year, she noted, the company has allowed users to process payments through its Messenger service, and has added other features to aid sales. “Since we were offering features like that, we thought we wanted to make clear that this is not a site that wants to facilitate the private sales of firearms.”

It is not clear how extensive arms trafficking on the site has been, but the rate of new posts has been unmistakably brisk, with many groups offering several new weapons a day. Jenzen-Jones said that ARES documented 250 to 300 posts about arms sales each month on the Libya sites alone, and that sales appeared to be trending up.

Overall, using data from arms-sales Facebook groups across the Middle East, he said, “We’ve got about 6,000 trades documented, but it’s probably much bigger than that.”

Bickert said the most important part of Facebook’s effort “to keep people safe” was to make it easy for users to notify the company of suspected violations, which can be done with a click on the “Report” feature on every Facebook post.

In this way so-called Community Operations teams — Facebook employees who review the reports in dozens of languages — can examine and remove offending content. How effective the policy is, in practice, is unclear. Several groups operated on Facebook for two years or more, accumulating thousands of members before Facebook announced its ban on arms sales.

This trafficking occurred in countries where the Islamic State is at its most active and where armed militias or other designated terrorist groups, including al-Qaida, have a persistent presence. In all four countries, government forces do not control large areas of territory and civil society is under intense pressure.

Christine Chen, a Facebook spokeswoman, said the company relied on the nearly 1.6 billion people who visit the site every month to flag offenders. “We urge everyone who sees violations to report them to us,” she said.

ARES has documented many types of buyers and sellers. These include private citizens seeking handguns as well as representatives of armed groups buying weapons that require crews to be operated effectively, or appearing to offload weapons that the militias no longer wanted.

Different markets have different characteristics. In Libya, fear of crime seemed to drive many people to buy pistols, Jenzen-Jones said.

“Handguns are disproportionately represented,” he said. “They are widely sought after — primarily for self-defense and particularly to protect against carjackings — with many prospective buyers placing ‘wanted’ posts.” They were also expensive, ranging from about $2,200 to more than $7,000 — a sign that demand outstrips supply.

In Iraq, the Facebook arms bazaars can resemble inside looks at the failures of American train-and-equip programs, with sellers displaying a seemingly bottomless assortment of weapons provided to Iraq’s government forces by the Pentagon during the long U.S. occupation. Those include M4 carbines, M16 rifles, M249 squad automatic weapons, MP5 submachine guns and Glock semi-automatic pistols. Many of the weapons shown still bear inventory stickers and aftermarket add-ons favored by U.S. forces and troops.

Such weapons have long been available on black markets in Iraq, with or without advertising on social media. But Facebook and other social media companies seem to provide new opportunities for sellers and buyers to find one other easily; for sellers to display items to more customers; and for customers to peruse and haggle over a larger assortment of weapons than what is available in smaller, physical markets.

Similarly, weapons identical to those provided by the U.S. to Syrian rebels have also been traded on Facebook and other social media or messaging apps.

In one recent example, a seller in northern Syria — who identified himself as a student, photographer and sniper — offered a pristine-looking Kalashnikov assault rifle that he said came from the Hazm Movement, which received weapons from the United States before the movement was defeated by the Nusra Front, an al-Qaida affiliate. He noted on Facebook that the rifle was new and had “never fired a shot,” and hinted of either a bonus gift or a discount.

In another example, from October, a Facebook arms-trading group offered a “new TOW launcher,” referring to a wire-guided anti-tank missile system of the same type provided to rebels by the United States and other countries. The post included a phone number for the seller, which linked to WhatsApp, a messaging service.

Reached on WhatsApp this week, the seller, whose profile picture shows the face of a corpse, said that he had sold the launcher but added, unconvincingly, that he could not recall the price.

Items offered for sale on Facebook in Libya also included much of the other equipment sought by militias or terrorists for their operations. These included ammunition, bulletproof plates for flak jackets, rifle scopes, hand grenades, two-way tactical radios, fragmenting anti-personnel warheads for rocket-propelled grenade launchers, uniforms (including police uniforms) and forward-looking infrared cameras, used for night imaging.

Bickert said that using Facebook to help sell items not considered weapons, like bulletproof plates, did not violate the company’s rules. Since the same groups selling the plates were also selling weapons, however, they were removed this week.

Online arms trafficking of this magnitude is an “eye opener,” said Nicolas Florquin, research coordinator for the Small Arms Survey, the Geneva-based international research center that underwrote the ARES study, part of an effort to supplement trafficking investigations by the United Nations Panel of Experts.

Without addressing Facebook or any particular social-media company directly, he added, “Obviously there has to be more attention to monitoring and controlling it.”

One of the arms-trading pages that Facebook took down this week included a stray advertisement, among ones for weapons and crates of 82 mm mortar rounds. It was for people looking to escape the miseries and dangers that have settled over some of the territory where such Facebook pages have been a feature of the arms trade. The advertisement offered open-ocean boat rides. Passage to Greece, it said, was “guaranteed.”

The advertisement was of a type. In a region struggling with large-scale violence and overrun by militias, terrorists and the many forces fighting them, Facebook groups dedicated to refugee trafficking promise the chance to escape.

To Learn More:

Twitter Pulls Plug on 125,000 Extremists’ Accounts (by Mike Isaac, New York Times)

Facebook Bans Private Gun Sales, Sending Gun Traders Scrambling to Find Online Platforms (by Dustin Volz and Julia Edwards, Reuters)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments