Every Case against U.S. Torture Perpetrators Has Been Thrown Out Except for this One … So Far

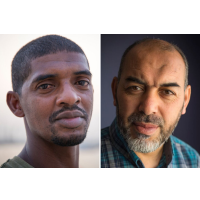

Plaintiffs Suleiman Abdullah Salim and Mohamed Ahmed Ben Soud (photos: ACLU)

Plaintiffs Suleiman Abdullah Salim and Mohamed Ahmed Ben Soud (photos: ACLU)

By Sheri Fink and James Risen, New York Times

Nearly 15 years after the United States adopted a program to interrogate terrorism suspects using techniques now widely considered to be torture, no one involved in helping craft it has been held legally accountable. Even as President Barack Obama acknowledged that the United States “tortured some folks,” his administration declined to prosecute any government officials.

But now, one lawsuit has gone further than any other in American courts to fix blame. The suit, filed in October 2015 in U.S. District Court in Spokane, Wash., by two former detainees in CIA secret prisons and the representative of a third who died in custody, centers on two contractors, psychologists who were hired by the agency to help devise and run the program.

One of them, James E. Mitchell, has written a book to be released Tuesday about his involvement in the program. In the book, he argues that he acted with government permission and that he and Bruce Jessen, the other psychologist and his co-defendant in the lawsuit, received medals from the CIA.

Legal experts say the incoming Donald Trump administration could force the case’s dismissal on national security grounds. Deciding whether to invoke the state secrets privilege over evidence requested in the lawsuit could represent the new president’s first chance to weigh in on the issue of torture. Trump has endorsed the effectiveness of torture and said he would bring back waterboarding, though it is not clear now that he intends to do so.

Lawyers for Mitchell and Jessen have clashed with the Justice Department over what classified evidence is needed to defend against the suit’s allegations that the men “designed, implemented, and personally administered an experimental torture program.”

Last month, despite U.S. government opposition, the court approved the defendants’ request for oral depositions of John Rizzo, a former CIA acting general counsel, and José Rodriguez, the former chief of the agency’s clandestine spy service who also headed the CIA’s Counterterrorism Center.

Mitchell was first publicly identified as one of the architects of the CIA’s “enhanced interrogation” program nearly a decade ago, and has given some news media interviews, but is now providing a more detailed account of his involvement. His book, “Enhanced Interrogation: Inside the Minds and Motives of the Islamic Terrorists Trying to Destroy America,” (Crown Forum) was written with Bill Harlow, a former CIA spokesman. It was reviewed by the agency before release. (The New York Times obtained a copy of the book before its publication date.)

In the book, Mitchell alleges that harsh interrogation techniques he devised and carried out, based on those he used as an Air Force trainer in survival schools to prepare airmen if they became prisoners of war, protected the detainees from even worse abuse by the CIA.

Mitchell describes sequestering prisoners in closed boxes, forcing them to hold painful positions for hours and preventing them from sleeping for days. He also takes credit for suggesting and implementing waterboarding — covering detainees’ faces with a cloth and pouring water over it to simulate the sensation of drowning — among other now-banned techniques.

“Although they were unpleasant, their use protected detainees from being subjected to unproven and perhaps harsher techniques made up on the fly that could have been much worse,” he wrote. CIA officers, he added, “had already decided to get rough.”

Obama declined to open a broad inquiry into the treatment of terrorism suspects, saying as president-elect that the nation needed to “look forward.” He did not rule out prosecuting those who went beyond techniques authorized by the Justice Department, but no one has been charged with those offenses under his watch. During the George W. Bush administration, a CIA contractor was convicted in the death of an Afghan detainee at a U.S. military base in Afghanistan.

Henry F. Schuelke, a Washington lawyer with the firm Blank Rome, who represents Mitchell and Jessen, said he believed his clients “were left holding the bag” while CIA officials involved in the program have been protected from the lawsuit. “The government and its officers, namely many of the CIA officers, enjoy sovereign immunity,” Schuelke said in an interview.

Schuelke and colleagues have argued in court that the senior U.S. District Court judge, Justin L. Quackenbush, should dismiss the case because, among other reasons, “sovereign immunity” extended to their clients, who were acting on the government’s behalf. But the judge denied the motion and the case has proceeded under the Alien Tort Statute, which allows foreigners to sue in United States court for violations of their human rights.

If the former detainees are successful, it would be the first time a U.S. civilian court has held individuals accountable for their role in developing counterterrorism policies after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks.

“All of the other cases have been thrown out on procedural grounds,” said Jonathan Hafetz, a professor at Seton Hall Law School. “If this is successful, it could pave the way for other torture victims to seek redress.” Still, some lawyers say it could be difficult for the plaintiffs to prevail.

The case has proceeded in large part because the psychologists’ role in the program has been documented, particularly in the declassified executive summary of a Senate Intelligence Committee investigation of the interrogation program released in 2014. While the Justice Department has fought to restrict the scope of sensitive information that it has been asked to produce in the case, it has thus far not asserted the state secrets privilege, a broad power to protect national security that could effectively shut down the suit.

That could change, analysts say, under the Justice Department in the Trump administration. Representatives for Trump did not reply to requests for comment on the case, scheduled for trial in June.

Lawyers for the detainees said they had no need for classified information. “There are dramatically more details in the public record about what the CIA and the psychologists did,” said Steven Watt, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union. “Now, any attempt to argue that torture is a state secret would be a transparent attempt to evade accountability.”

But lawyers for the psychologists contend they require access to secret information to prepare an adequate defense.

In his book, Mitchell, who had been identified years before the Senate Intelligence Committee report and formed a company that received $81 million for counterterrorism after Sept. 11 (his personal percentage of profit from the contract “was in the small single digits,” he wrote), nonetheless criticizes Senate staff for allegedly leaking his name, which he said made him a target of terrorist threats. He also says the techniques he used sometimes caused resistant detainees to cooperate in providing useful intelligence, though the book offers little if any new evidence that this is the case.

Mitchell says Democratic Senate staff “cherry-picked documents to create a misleading narrative” from tens of thousands of pages of the CIA’s own documentation that the committee reviewed over several years while compiling its report. The report concluded that the CIA’s use of harsh interrogation techniques was brutal, costly, ineffective at gathering intelligence and “damaged the United States’ standing in the world.” The CIA did not provide comment on Mitchell’s book by the time of this article’s publication.

In one instance, Mitchell describes his and Jessen’s experiences with Gul Rahman, an Afghan citizen captured in November 2002 in Peshawar. He was found dead, naked from the waist down on a bare concrete floor in the freezing cold at a secret CIA prison that month, shackled and short-chained to a wall. A representative of Rahman’s estate is a party to the lawsuit that the ACLU lawyers filed against the two psychologists.

Mitchell writes that he and Jessen raised concerns about Rahman’s well-being before their departure from the site, just days before his death. “To imply that his death was part of the program I was involved with is simply false,” Mitchell writes.

But a January 2003 CIA memorandum outlining an investigation into Rahman’s death, released to the ACLU in late September, found that Jessen interrogated Rahman after he was subjected to “48 hours of sleep deprivation, auditory overload, total darkness, isolation, a cold shower, and rough treatment.” (The document had previously been released, but in a more redacted form without the psychologists’ names.) During that interrogation, Rahman resisted answering questions and “complained about the violation of his human rights.”

Jessen also said he “thought it was worth trying” a rough takedown, during which Rahman was forced out of his cell, secured with Mylar tape after his clothes were cut off, covered with a hood, slapped, punched and then dragged along a dirt floor, the memo said. Rahman died of what an autopsy suggested was hypothermia.

The other two plaintiffs, Suleiman Abdullah Salim, a Tanzanian, and Mohamed Ahmed Ben Soud, a Libyan, continue to suffer from psychological problems related to their torture, The New York Times has reported.

The plaintiffs are seeking compensatory and punitive damages. “This case shows that there are consequences for torturing people,” Watt of the ACLU said, adding that it “should serve as a warning to anyone thinking about bringing back torture.”

To Learn More:

Int’l Criminal Court Considers War Crimes Probe of U.S. Military and CIA Torture in Afghanistan (by Mike Corder, Associated Press)

Psychologists Who Developed CIA Torture Program Get Court Approval to Depose their CIA Bosses (by Jamie Henneman, Courthouse News Service

Psychologists Who Designed Torture Methods for CIA Admit to Torturing but Deny It Was Torture (by Nicholas K. Geranios, Associated Press)

In Pursuit of Investigation and Prosecution of CIA Torture Program Perpetrators (by Noel Brinkerhoff and Steve Straehley)

The Case for War Crimes Trials (by Noel Brinkerhoff and David Wallechinsky, AllGov)

Obama: Torture Okay if Just Following Orders (by Noel Brinkerhoff and David Wallechinsky, AllGov)

Should George W. Bush be Tried for War Crimes? (by David Wallechinsky, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

- Donald Trump Has a Mental Health Problem and It Has a Name

Comments