European Nations Move to Corporate Transparency While U.S. Clings to Veil of Secrecy

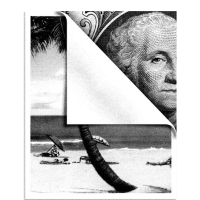

(photo: Heads of State)

(photo: Heads of State)

By Celestine Bohlen, New York Times

PARIS — Journalists have done their job, again, with another enormous leak of documents outing a global list of rich and powerful people who hid their wealth in offshore companies.

This time, prompted by the Panama Papers, several European governments have followed up with new measures intended to rip away the veil of secrecy that is costing them billions of dollars in tax revenues.

“Populist outrage doesn’t by itself collect a single extra pound or dollar in tax or put a single criminal in jail,” said George Osborne, the chancellor of the Exchequer in Britain, at a news conference Thursday in Washington.

To that end, the biggest economies in the European Union — Britain, France, Germany, Italy and Spain — announced a plan to automatically share information about the true, or “beneficial,” owners of shell companies and overseas trusts.

This is good news for the global campaign to expose the ill-gotten gains of the corrupt and the secretly held wealth of tax evaders who benefit from a system that rewards anonymity.

But there is one major player that is coming up short, and that is the United States, which in 2015 ranked third, behind Switzerland and Hong Kong, in a financial secrecy index published by the Tax Justice Network, a nonprofit organization based in Washington.

The Obama administration has recently taken steps to require banks to check the identities of clients setting up companies and to track the ownership of expensive real estate.

Resistance to greater corporate transparency is still strong at the state level, however, where companies and corporations are registered.

Attention has focused on Delaware, Wyoming and Nevada, which aggressively market tax advantages for offshore companies. But in fact, full disclosure of ownership is not required in any of the 50 states.

This has created an enormous black hole not only for tax inspectors but also for law enforcement officials who “can’t follow the money,” said Tom Cardamone, managing director of Global Financial Integrity, a research and advocacy group based in Washington.

“What we have in place is complete secrecy, and it is secrecy that is the problem,” he said.

A bipartisan bill to make the states require disclosure of ownership is now before Congress, but it has stalled.

Opposition comes from the American Bar Association, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and a less-known but powerful lobby, the National Association of Secretaries of State. That final group fears a loss of revenue for state budgets if more transparency is required, said Robert Palmer, campaign director at Global Witness, an anti-corruption organization.

“Passing legislation in the U.S. is challenging,” he said.

Failure to respond to the worldwide clamor for financial accountability looks hypocritical from afar, considering the United States’ aggressive extraterritorial pursuit of foreign companies that violate its Foreign Corrupt Practices law and its demands that foreign banks provide information about accounts held by U.S. citizens.

“Though the U.S. has been a pioneer in defending itself from foreign secrecy jurisdictions it provides little information in return to other countries, making it a formidable, harmful and irresponsible secrecy jurisdiction,” according to a Tax Justice Network report.

Though legislation in the United States has faltered, other countries began moving ahead with the creation of registries of corporate beneficial owners even before the Panama Papers came to light. Such a registry will be available to the public in Britain on June 30, while national registries required by the European Union will be ready by 2017, although access to their information will be more restricted.

Pressure is now growing on Britain to force its overseas territories — like the British Virgin Islands, which is home, on paper, to more than half of the companies revealed by the Panama leak — to follow suit, a subject sure to dominate an anti-corruption summit meeting in London next month.

Transparency advocates hope similar pressure will build in the United States to shine a light on what Osborne called “those hiding spaces, those dark corners of the global financial system” right in its own backyard.

As Palmer says, “I don’t think we should have to rely on journalists.”

To Learn More:

Why So Few Americans in Panama Papers? Firm “Defends” its Rejection of U.S. Clients (by Juan Zamorano and Joshua Goodman, Associated Press)

Forget Panama: U.S. is a Leading Tax Avoidance Haven for Foreigners (by Paul Wiseman and Marcy Gordon, Associated Press)

Offshore Accounts of World Leaders Detailed in Leaked Documents (by Frank Jordans, Associated Press)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments