Human Vultures Descend on Poor Victims of Lead Poisoning

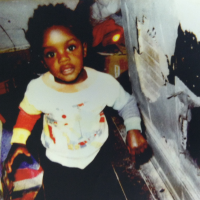

Childhood photo of Freddie Gray standing next to crumbling wall with possible lead contamination (Family photo from court filings)

Childhood photo of Freddie Gray standing next to crumbling wall with possible lead contamination (Family photo from court filings)

The lead paint that’s responsible for learning disabilities among many who grew up in substandard housing is paying dividends now for companies seeking to prey on those victims.

Countless studies have demonstrated lead’s effect on the cognitive and emotional states of those exposed to it. Appropriately, landlords who allowed lead paint to remain in their buildings have been forced to pay their victims thousands of dollars to attempt to compensate them for the brain damage caused by peeling lead paint. These payouts are often in the form of “structured settlements” which provide the victims with monthly payments for the rest of their lives.

Structured settlement companies are known to millions through their ads on late-night television. But those companies don’t just sit around and wait for the phone to ring—they go where the money is, and in Baltimore, it’s with victims of lead paint poisoning. This is a place that is ripe for the pickings by such companies, which circle above the city like vultures waiting to swoop in for the kill. During the past two decades, the Maryland Department of the Environment has added to its lead registries more than 93,000 children who suffer from the poisoning.

The Washington Post reported that one company, Access Funding, has made it its business to seek out victims of lead poisoning in Baltimore. Many people there, including Freddie Gray—whose death earlier in April while in the custody of Baltimore police triggered violent civil unrest—grew up in buildings with peeling lead-based paint and suffered brain dysfunction as a result. Some of those victims received structured settlements from landlords and their insurers, money meant to last the rest of the victims’ lives. But Access has sought out those people and offered them pennies on the dollar to sell their settlements, according to the Post’s Terrence McCoy.

“A lot of them can barely read,” Saul E. Kerpelman told the Post. The Baltimore attorney has defended an estimated 4,000 victims of lead poisoning, the majority of whom are black. “They have limited capacity. But they fall through a crack. If they were severely disabled enough, you could file a court petition to have a trustee manage their property. But they’re not disabled enough.”

With no one to look out for them, the victims are easy targets for Access and similar companies. They’re offered a percentage of their settlement, often about a third, to give up their monthly income. Because they’re impaired by the lead poisoning, they often don’t understand the contracts they’re offered.

One of Access’ marks, referred to only as Rose in McCoy’s article, is a 20-year-old who has mental deficiencies caused by irreversible brain damage from childhood lead poisoning. Unbeknownst to her mother, an Access representative had called her on the phone one day and offered to make her some quick cash, so she agreed. That agreement resulted in Access acquiring her monthly settlement payments, the ultimate value of which totaled more than half a million dollars, in return for which Rose was paid an immediate flat fee of less than $63,000.

Freddie Gray had agreed to sell Access Funding his structured settlement—$146,000 worth (valued at $94,000) for about $18,300, reported the Post. His siblings, also lead poisoning victims with a settlement arrangement, followed suit. “They sucker you in. . . . They didn’t know they were giving up so much for so little,” their stepfather Richard Shipley told the Post. Now that the sales have been made, Access won’t return his phone calls, he said.

A Maryland law requiring that the deals be reviewed by an independent attorney isn’t worth the paper it’s printed on; the same attorneys are somehow retained in many of the deals offered by particular companies. Access has also sought out judges, primarily in suburban counties, not in Baltimore proper, that give little scrutiny to the deals. Access Funding has petitioned Judge Herman C. Dawson more than 160 times since 2013 to purchase structured settlement payments, according to the Post. Dawson has approved 90% of the requests.

For its part, Access denies any improprieties. “We’re trying to bring better value to people,” Access Funding chief executive Michael Borkowski told the Post. “. . . We really do try to get people the best deals.” Borhowski denied knowing his clients were impaired, even though his clients’ impairments are the very reason he and his company got their settlements in the first place.

Some of the victims of Access’ tactics are fighting back. At least one is suing the “independent” attorney who advised her on the deal.

-Steve Straehley, Danny Biederman

To Learn More:

How Companies Make Millions off Lead-Poisoned, Poor Blacks (by Terrence McCoy, Washington Post)

Freddie Gray’s Life a Study on the Effects of Lead Paint on Poor Blacks (by Terrence McCoy, Washington Post)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments