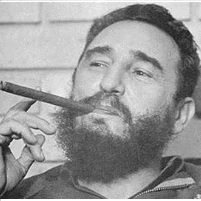

Dictator of the Month: Fidel Castro

Tuesday, May 17, 2011

Fidel Castro seized power in Cuba in January 1959, at the age of 31 or 32, and held on until health problems forced him to begin giving up partial control in 2006. He finally retired officially as the leader of the Communist Party of Cuba on April 19, 2011, handing over power to his younger brother, Raúl, who will turn 80 on June 3.

In my book Tyrants: The World's 20 Worst Living Dictators, I included a chapter about Castro. Here is an excerpt.

THE NATION—Cuba is an island about the size of Pennsylvania in the Caribbean Sea, ninety miles south of Florida. The nation of Cuba, which has a population of more than 11 million, includes several smaller islands. Internationally, it was known as little more than a producer of sugar and as a gambling haven until, in the midst of the Cold War, Cuba’s dictator, Fidel Castro, turned his country into the Soviet Union’s leading client state in the Americas.

A DICTATOR IS BORN—Fidel Castro was born on August 13, but like much of his life, the year in which he was born is surrounded by controversy. Castro himself claims the year was 1926, but his sisters have said that he was actually born a year later in 1927. He was definitely born in Manacas, a farming community in the municipality of Birán, in the Mayarí region of northern Oriente, which is literally closer to Haiti, Jamaica, and even the Bahamas than it is to Havana.

Castro’s father, Ángel Castro y Argiz, was born in Lancara, Galicia, Spain, and emigrated to Cuba in 1898. He spent five years working in a brick factory owned by his uncle before moving to Mayarí, which was then dominated by the United Fruit Company. Ángel began to work on the railroad being built by the company, laying down tracks and performing manual labor, before starting a business selling lemonade to workers in the fields. He used the profits to expand his business, going from town to town selling goods and merchandise. Eventually, Ángel leased land from the United Fruit Company, planting sugarcane and employing small farmers. The lands owned or rented by the Castro family grew to some 26,000 acres, with about 300 families living and working on the property. By the time Fidel was born, the family was quite wealthy. The Castros lived in a two-story country house, built in the Galician style with wooden stilts and a space underneath for farm animals. Ángel’s first wife, María Argota, gave birth to two children, Pedro Emilio and Lidia. Although accounts are sketchy, it appears that María died after the birth of her second child, although Juana Castro, Fidel’s younger sister, insists that she simply left the family. With María gone, Ángel soon took up with young Lina Ruz González, who had been working in the Castro household as a maid or cook. The pair had three children out of wedlock, Ángela, Ramón, and Fidel. They married shortly after Fidel’s birth.

The Castro household was unusual. Although wealthy and powerful for the region, their lifestyle remained extremely rural, with livestock and chickens wandering throughout the house. To bring the family in for meals, Lina would shoot a gun outside the kitchen door. Meals were always eaten from a communal pot while standing.

Fidel was named after Fidel Pino Santos, a wealthy Oriente politician and a close friend of Ángel Castro. Fidel also means “faithful,” a fact that Castro would later use in speeches. Fidel was not christened until he was five or six years old, and as a result the other children in Birán called him “Jew.”

Like his father, Fidel was prone to violent tempers, and he could be a very sore loser. His sisters recall him starting a baseball team in Birán with equipment bought by his father. If the game was going poorly or his team began to lose, Fidel would simply stop the game, gather up the equipment and walk off. Castro’s close friend, novelist Gabriel García Márquez, wrote, “I do not think anyone in the world could be a worse loser. His attitude in the face of defeat, even in the slightest events of daily life, seems to obey a private logic: he will not even admit it, and he does not have a moment’s peace until he manages to invert the terms and turn it into a victory.”

As a child, Fidel was sent to study in Santiago, the second-largest city in Cuba. He spent his first two years in Santiago living with his godparents, during which time he was homeschooled. Eventually, he was enrolled in the Marist school La Salle, along with his older brother Ramón and his younger brother Raúl. Fidel quickly gained a reputation as a troublemaker and a bully, starting fights with the other boys as well as with the priests.

Ángel received a report that his sons were cheating and that they were “the three biggest bullies” who had ever gone to the school, so he decided not to send them back to La Salle. Fidel, who was in the fourth grade, responded by threatening to burn down the house. Ultimately, Fidel was reenrolled in school, but this time at a more demanding Jesuit institution. When his father threatened to cut off his allowance if his grades slipped, Fidel forged his report cards with the highest marks to take home, while forging his father’s signature on his real report card.

Although he was a mediocre student, the young Fidel was known for his almost photographic memory. A fellow classmate, José Ignacio Rasco, recalled Castro impressing the other students by reciting the pages of their textbook from memory. The children would call out a page number and Fidel would repeat the exact contents of the page, including whether or not the last word ended in a hyphen.

In November of 1940, Castro wrote a letter to U.S. president Franklin Delano Roosevelt: “My good friend Roosevelt, I don’t know very English, but I know as much as write to you. I like to hear the radio, and I am very happy, because I heard in it, that you will be president of a new era. I am a boy but I think very much but I do not think that I am I [sic] to the President of the United States. If you like, give me a ten dollars bill green America, in the letter, because never, I have not seen a ten dollars bill green American and I would like to have one of them.” Castro received a letter in reply but no money.

Fidel continued his education at the exclusive Jesuit Belén College in Havana. It was here that Fidel learned the skills of public speaking and oration for which he eventually became famous. He attempted to enroll in the Avellaneda Literary Academy, the oratory school at Belén, but was rejected twice after failing to complete a 10-minute speech without notes. Eventually, he earned acceptance and learned to control the stage fright that had paralyzed him.

In another violent episode, Castro got into a fight with a student who called him “crazy.” Fidel bit the student and ran out of the room, only to return with a pistol and brandish it until a priest subdued him. Despite rumors to the contrary, he did not graduate at the top of his class. He was remembered, however, for having received the longest and most enthusiastic ovation from his fellow classmates.

UNIVERSITY DAYS—In October of 1945, Castro entered law school at the University of Havana. At the time, the university was an autonomous and self-governing body, and neither the police nor the army was allowed to enter the campus. As a result, the university became a haven for gangsters and political movements. Between 1944 and 1948, more than 120 mob-style murders were attributed to the gangs. It was also while at university that Castro met some of the people who would become closest to him, including Alfredo Guevara (no relation to Ernesto “Che” Guevara). Guevara would later recall Castro as “a boy who will be José Martí or the worst of the gangsters…”

Around this time, President Ramón Grau San Martín approved a rise in bus fares that provided the impetus for Castro’s first political action. He organized a demonstration against the fare increase and led a group of students on a march to the presidential palace. The students were beaten by police forces and Castro was slightly injured. Castro was quick to use the incident to his advantage, gaining newspaper coverage. Three days later, Castro was part of a student delegation that went to meet President Grau. As they waited in the president’s office for Grau to arrive, Castro joked with the other three students that when Grau entered they should pick him up and throw him from the balcony, then get on the radio and proclaim the victory of the student revolution.

Two main gangster groups were vying for control of the University of Havana, the Socialist Revolutionary Movement (MSR) and the Insurrectional Revolutionary Union (UIR). The MSR was led by Rolando Masferrer, one of Batista’s worst henchmen, while the UIR was headed by Emilio Tró. Conflicts between the two groups were frequent and violent. When Castro entered the university he began to maneuver between the two groups. Initially he tried to foster a relationship with the MSR’s Manolo Castro, then president of the Students’ Federation. In December of 1946, Lionel Gómez, a member of the UIR, was shot in the lung. He named Fidel Castro as his attacker, although there was little evidence actually linking Castro to the crime. Nonetheless, it was widely believed that Fidel had attempted the assassination to ingratiate himself with Manolo Castro and thereby gain entrance into the MSR. Surprisingly, it was Emilio Tró, the head of UIR, who took Fidel under his wing, giving him a pistol, which he took to carrying with him at all times.

Castro’s association with the UIR brought him into conflict with the MSR. Rolando Masferrer sent him an ultimatum: leave the gang scene or face the consequences. Instead, Castro volunteered for a planned invasion of the Dominican Republic. The campaign was being led by a group of Dominican exiles, including future president Juan Bosch, and was largely a response to the horrors of the regime of Rafael Trujillo, who had been in power since 1930. During this time, Trujillo’s troops had massacred at least 12,000 Haitians along the border, and Trujillo had personally killed people at his opulent home, dumping their bodies in the river.

On July 29, 1947, Castro and his companions sailed to Cayo Confites, the launching point for the invasion. The Cayo Confites forces numbered about 12,000 men, mostly students. Fidel received his first military training, although it lasted only a week. The rest of the time was spent waiting on the mosquito-infested island for the order to launch. Unfortunately for the would-be invaders, Trujillo had long since heard about their plans and had had time to prepare his defense and even to complain to the United States. On September 27, after the invading fleet was already on its way, the leadership called off the attack. With the campaign officially over and the Cuban military rounding up the revolutionary vessels, Castro chose to jump ship and swim for shore. After swimming for eight or nine miles, he reached shore the next day and appeared at his family home.

While Fidel was on Cayo Confites, Emilio Tró was killed in Havana by MSR thugs in a gun battle that lasted hours. Less than six months later, Manolo Castro was killed outside of a Havana movie theater that he owned. Castro, sensing a more promising direction for his future, moved away from the gangsters and became more involved in political actions. He once declared that Al Capone was a stupid man because he had never formed an ideology. If he had, Castro insisted, he would be have been world famous, and not remembered only as a gangster.

In 1947, Castro participated in a trip by law students to the Isle of Pines, the location of Cuba’s new “model” penitentiary. Returning to Havana, Fidel criticized the prison and the treatment of the inmates. Six years later, Castro would end up a prisoner in the same penitentiary. In 1948 he traveled to Bogotá, Columbia, with three other students from Havana University, including Alfredo Guevara. The trip was part of a Latin American student congress and was financed by Juan Perón, the leader of Argentina. Arriving in Columbia on April 7, Castro and the other students met with Jorge Gaitán, the leader of the Liberal Party and the man expected to win upcoming elections. They were invited to return on April 9 for a meeting at 2:00 p.m. Less than an hour before their scheduled meeting, Gaitán was shot and killed by a mentally deranged man, Juan Roa Sierra. Bogotá erupted in riots, in which Castro was swept up for two days. During the riots, he became involved in the takeover of a police station. By the time the riots subsided, approximately 3,500 people had been killed and a third of the city had gone up in flames.

SERIOUS POLITICS—Back in Cuba, Castro aligned himself with Senator Eduardo “Eddy” Chibás, the voice of the anti-Grau opposition. Despite coming from a wealthy family, he had spoken out against the corruption of Cuba’s political elite, running on the slogan “Shame of Money.” Disgusted with the state of Cuban politics, Chibás had created the Cuban People’s Party, known as the Ortodoxos because they claimed to stand for the orthodoxy of Jose Martí’s principles. Castro joined the Orthodox Party and campaigned hard for Chibás in his unsuccessful bid for the presidency in 1948. While Fidel presented himself as Chibás’ protégé and political heir, in private the two were never close. Chibás resented the young Castro, while Fidel saw Chibás as an obstacle to his own power. In order to be taken seriously as a politician, Castro knew he had to break free of his gangster ties. In late November 1949, he decided to make a clean break, denouncing the actions of the gangsters in front of a large crowd at the university and naming names and pacts. Not surprisingly, the speech put Castro in a dangerous situation and he was forced into hiding, eventually fleeing to New York City for three months.

Castro eventually graduated with a law degree and briefly started a law practice, although he actually practiced little law, concentrating instead on politics. Meanwhile, he led a relatively quiet social life. He was never known to dance, something exceedingly uncommon in Havana in the 1940s, and he was generally awkward and shy around women. Finally, he met Mirta Díaz-Balart and married her in 1948. Mirta was considered an exceptionally beautiful woman, with blonde hair and green eyes. She came from one of the wealthiest families in Cuba, with close ties to Batista. At their wedding, Mirta’s father gave the young couple $10,000 for a three-month honeymoon in the United States, with $1,000 in spending money provided by Cuba’s dictator, Fulgencio Batista. The couple spent most of their honeymoon in New York City, where Fidel learned English and sat in on courses at Columbia University. Castro later recalled going into a bookstore in Manhattan and being shocked to see Karl Marx’s Das Kapital available.

Upon their return to Cuba, the newlyweds moved into a hotel located across the street from a military camp. On Sept 1, 1949, Mirta gave birth to Fidel Castro Díaz-Balart, nicknamed Fidelito. Castro would never be close to his first son, but he was protective of him.

On Sunday, August 5, 1951, Senator Eduardo Chibás went on his weekly radio program and spoke out, as usual, against the corruption of the political system, accusing the education minister, Aureliano Sánchez Arango, of using political funds to buy a large mansion. At the end of his radio show, Chibás urged the Cuban people to wake up to the corruption in government. He then took out a .38 Colt and shot himself in the abdomen. Unfortunately for Chibás, his speech had gone on a little too long. Several minutes before the pistol shot rang out, the radio engineer had cut him off to play a series of radio commercials, including one advertising a brand of coffee that was “good to the last stomachful.” Chibás was taken to a hospital, where he lingered for eleven days before dying. During this time, Castro kept close to the politician’s bedside. When Chibás lay in state in the University Hall of Honor, Castro stood by as part of the honor guard for more than twenty-four hours and he appeared on the front page of several newspapers.

As the military prepared to move Chibás’ body in a large procession, Castro tried to convince Captain Máximo Rávelo, the army captain commanding the escort of the gun carriage transporting the casket, to divert the procession route to the presidential palace. Castro was apparently convinced that he could trigger a mass uprising. Fearing military action and a possible bloodbath, Rávelo refused. President Carlos Prío himself had packed a bag and prepared a plane in the event that a mass uprising did occur.

Castro continued his political pursuits by running for the Chamber of Deputies in 1952. He sent out 100,000 letters to all the members of the Orthodox Party asking for their support. With broad support from the urban and rural poor, Castro was in line to be elected. In fact, he would have been a strong contender for an eventual seat in the senate, and perhaps ultimately might have been elected president through democratic means. However, the planned elections were disrupted on the morning of March 10, 1952, when Batista walked into the army’s Camp Columbia in Havana along with his officers. They met no resistance, and by the time dawn broke Batista had taken power and Prío had fled the country. When news of Batista’s coup spread, Fidel and his brother Raúl immediately went into hiding. Hours later the secret police arrived at both their houses looking for them.

By this time, Castro had become involved with Natalia Revuelta. “Naty” was known as one of the most beautiful women in Havana, tall, fair and prosperous. She was well educated, having been raised in France and the United States, and was married to a well-known Cuban heart surgeon, Orlando Fernández-Ferrer. She was also a secret admirer of Castro, and she offered him the use of her apartment as a hiding place. Eventually, Naty became central to Fidel’s revolution, providing money and helping print and distribute pamphlets, and even agreeing to let him store firearms and ammunition in her house. The two became lovers, and when Mirta found out, she asked for a divorce in July 1954.

ORGANIZING THE REVOLUTION—Although Castro had been well on his way to being an elected official, Batista’s coup gave him the opportunity to play his favorite role: revolutionary leader. He lost no time in gathering a movement for liberation, choosing to create his own organization rather than working with the Communists. Castro saw the Communists as out of touch with the masses and too large for him to control, while the Communists, who enjoyed some support from Batista, had no need of the young revolutionary.

Castro gathered his forces from Eddy Chibás’ former Orthodox Party and from within the University of Havana. He and his supporters set up a small revolutionary newspaper, which they printed on a mimeograph machine that they hid inside the trunk of a car. Castro also secured two small two-way radios and began broadcasting regular programs. Within fourteen months, Castro had amassed about 1,200 men. During this time of organizing, he drove more than 30,000 miles, some forty times the length of the island.

From the outset, Castro ran his movement like a military organization, with no democratic processes whatsoever. He passed down orders to his officers and they were expected to obey without question. Castro forbade the drinking of alcohol and imposed strict sexual standards, several times forcing his men to marry their girlfriends. He also ordered that weekly meetings be held to analyze the conduct of the movement’s members, and infractions could be punished by expulsion or even death. When another group of student revolutionaries was betrayed by an insider and thrown in prison, Castro became even more security conscious, rarely attending the military training sessions that his group held on university grounds, using the basements of buildings as well as the rooftops of the science building. Many members did not even know that Castro was their leader. Castro developed and employed guerrilla tactics that are still used by underground movements and terrorists today. He based his organization on a cell structure, and nobody within a cell knew people in other cells. Meeting places were kept secret until the last minute.

Soon, Castro faced a critical problem. Although he had the men, he did not have the weapons needed to undertake an armed revolution. Not only that, he did not have enough money to purchase arms for all his men. Castro’s solution was to attack a military base and seize its weapons. He chose the military base in Moncada because it was located in the traditionally rebellious province of Oriente and, in those days of limited communications, it was far enough away from Havana that it would take some time for the action to become known to Batista. Castro also fantasized that the attack would spark a larger armed rebellion throughout the province. The arms seized from the military base would be handed out to the population, who would then join in securing the zone from Batista’s military. Simultaneous to the Moncada attack, a smaller force would attack the Bayamó Barracks, farther to the west, gaining more munitions and closing off the roads into the province, thus creating a “Liberated Zone” within Cuba.

The Moncada attack was planned for the morning of July 26, 1953, but it ran into problems from the start. The 162 revolutionaries bundled into a 26-car motorcade. One car had a flat tire almost immediately after leaving the farm that served as the staging area. Another car took a wrong turn into the center of town and did not arrive until after the attack had already begun. Finally, a group of four students decided not to participate in the attack at all. Fidel told them to wait until the rest of the cars had left, but they wound up leaving in the middle of the convoy. When they took the turn for Havana, the car behind them mistakenly followed. By the time the would-be revolutionaries in this car realized their error, they had gone well past Santiago and were too far away to participate in the attack. Once the remaining cars arrived at Moncada, their problems continued. The plan had been to attack the morning after Carnival, while most of the government soldiers would be sleeping off the previous night’s excesses. As it turned out, however, many of the soldiers were just getting back from their partying, and they had brought back with them to the base even more soldiers to join them in further festivities. The attack was completely unsuccessful. Eight of the revolutionaries were killed and, within a week, the rest had all been captured. Sixty-nine of the rebels were brutally tortured and then killed in prison.

Castro and his co-conspirators were tried before a military tribunal. Castro used the trial as an opportunity for publicity, railing against the Batista regime, denouncing the torture and murder of the prisoners and demanding that the perpetrators be brought to justice. Castro was sentenced to fifteen years in prison. However, his defense statement, “History Will Absolve Me,” would become the most famous of his speeches. The text would later be smuggled out of the prison, written in lemon juice between the lines of letters he would write to his friends and family.

Castro ended up in the Isle of Pines prison, which had originally been built by General Machado in 1931 to house the increasing numbers of political prisoners. When Castro and his rebels arrived, they quickly adopted it as a training ground and school. Castro maintained more strict controls on the behavior of his men than did the guards themselves. If the men were ordered by the guards to get up at 6:00 a.m., Castro would make them get up at 5:30. The rebels became noted for their impeccable behavior and were given more freedoms. They eventually began offering classes in Cuban history, grammar, geography, and English. At one point, Castro was put in solitary confinement for fourteen months as punishment for organizing fellow prisoners to sing a revolutionary anthem during a visit by Batista.

In 1954, running unopposed, Batista was elected president. By the following year, enjoying the support of the U.S. government, he felt secure in his control over the country. On May 6, in a bargain with the Orthodox Party and under pressure from the public and Congress, Batista granted Castro and the rest of the rebels amnesty, announcing that it was a Mother’s Day present. Less than two years after their failed attack on Moncada, Castro and his men walked out of prison.

THE MEXICAN SOJOURN—Castro continued to publish attacks on the government, but after two dissidents were severely beaten by Batista’s thugs and one was killed, he was increasingly worried about his safety and never slept in the same house two nights in a row. Two months after leaving the Isle of Pines, Castro decided to leave Cuba for Mexico. To finance the trip, his sister Lidia sold her refrigerator. Once in Mexico, Castro contacted Alberto Bayo, a former soldier in the Spanish Civil War and an expert on guerrilla warfare who was running a small furniture shop in Mexico. Castro asked Bayo to take charge of training his men. Castro’s forces in Mexico began as a small group of sixty or seventy, living in six rented houses. The members of each house were kept under strict control, forbidden to leave without permission or to visit any of the other houses. They could not use the telephone or speak to anyone on the street. Each house included a rebel tribunal that enforced the rules and meted out punishment, which, in at least one instance, included death. Castro next contacted former Cuban president Prío, who was living in Texas. The two met only once, but the elder politician agreed to give Castro $100,000 to finance the revolution. In exchange, Castro agreed to give Prío advance warning before his assault, so that the two could coordinate their efforts. In fact, Castro had to intention of doing so, and instead planned his attack to coincide with a simultaneous uprising on the island, led by Frank País, the head of a separate revolutionary movement.

It was in Mexico that Fidel met a man who would become central to the Cuban revolution. Ernesto “Che” Guevara was born in Rosario, Argentina, into an upper-class family. The son of a doctor and the eldest of five children, Guevara suffered from frequent and debilitating asthma attacks which would plague him his entire life. A doctor by the age of twenty-three, he set out on an odyssey through Latin America, eventually moving to Mexico with his Peruvian wife Hilda. When Castro and Guevara met, Guevara was already a self-described Marxist and was far more of an ideologue than Fidel.

THE REVOLUTION—Castro chose to launch his revolution from the Mexican port of Tuxpan. He found a small, sixty-foot boat called the Granma that he bought from an American for $20,000. The boat was designed to carry at most twenty-five people and was powered by two small diesel engines. When the eighty-two rebels finally took off, the boat sat so low in the water that they were in constant danger of capsizing. Like the Moncada attack, the assault on Cuba ran into problems from the start. Traveling at 7.2 knots, the tiny ship was battered by bad weather. Two days into the voyage it became clear that the crossing would take at least seven days, instead of the estimated five, and that the landing would therefore miss the planned uprising in Cuba. On the fifth day, still at sea, the rebels heard news over the radio of País’ attempted revolt, and its bloody defeat by Batista.

On December 2, 1956, the rebels landed, or as Che would describe it, shipwrecked, at a muddy place called Purgatory Point. Within an hour, Batista had learned of the force and had sent planes to strafe and bomb the area. According to Castro, only twelve men survived the initial landing and attack. The number was probably chosen more for its religious significance than its accuracy, and other historians have estimated the force to be either eighteen or twenty. The men marched for three days through the forest, covering just twenty-two miles while being continually hounded by bombings and ground troops. On the third day they were surrounded and attacked by a group of soldiers, during which Che was wounded in the shoulder. The rebels hid in a sugarcane field, but with no food or water they were forced to drink their own urine to survive.

Eventually, the rebels reached the Sierra Maestra, where they settled among the rural peasants and began to regroup. The locals, who felt no allegiance to Batista, received them warmly, providing food and supplies. On January 17, 1957, Castro led his men, now numbering thirty-three, on their first attack, against a small garrison in La Plata. The rebels killed two soldiers and wounded five, and carried off a number of guns and munitions. They also behaved according to their strict rules of morality, allowing wounded soldiers to receive medical aid and releasing all prisoners after the initial attack.

A month later Castro felt the time was right for some controlled media coverage, so he sent a rebel to Havana to bring back a foreign journalist. The man chosen was Herbert Matthews of the New York Times, who was sent to the Sierra Maestra to confirm that Castro was actually still alive. Although the rebels still numbered less than fifty, Castro ordered columns of men to march past the camp, then change uniforms and march back again, to make it appear that their forces were larger than they really were. At one point Castro even had one of his officers interrupt the interview to say that a separate regiment of troops had just arrived, a regiment that never in fact existed. The ploy worked, and Matthews wrote a three-part story about the massive build-up of rebels in the mountains.

As the movement grew, Castro began to clash with other members of the revolution, especially Frank País. País, who had survived the failed uprising in December, had continued to lead the guerrilla movement in the cities, a much more difficult and dangerous operation. A strong, handsome, and charismatic leader, he was one of the few people who dared to challenge Castro’s control, and he often clashed with Fidel on how to organize the rebellion. País came from an upper-class background and was vehemently anti-Communist. He wanted to replace Castro’s strict top-down hierarchy with a more democratic and decentralized structure. Unfortunately, País was being tracked ever more closely by Batista and his men. Despite appeals for support to Castro, País was eventually surrounded in one of his hideouts and killed by an assassin.

Popular support for the rebels continued to grow, and more and more Cubans joined their forces. In March 1958, Raúl Castro was given command of the Second Front, based in Oriente, which began to operate semi-independently of the Sierra Maestra group. Although still under his brother’s command, Raúl showed his talent as a military tactician, capturing or destroying many of Batista’s planes, trains, and military vehicles.

In April of the same year, Fidel called on the people of Cuba to participate in a general strike, which he hoped would spark a nationwide uprising. When Batista heard about the strike he gave orders to execute anyone who participated. More than 140 activists, mostly young people, were gunned down. However, Batista’s harsh response only served to increase Castro’s popularity.

By the end of the summer it was clear that the tide was beginning to turn. In September, Che Guevara and Camilio Cienfuegos led two forces of rebels on what would become known as the “Westward March.” Batista’s troops put up practically no resistance, either giving up town after town or actually deserting to the rebels. By November the rebels controlled almost all of the transportation lines in Oriente and were moving slowly but surely toward Havana.

VICTORY—On the night of December 31, 1958, Batista resigned and fled the country. Fearing a takeover by a military junta, Castro and his men left at dawn for Santiago, arriving on January 2. That night Castro gave a speech in front of 200,000 people. He was flanked on one side by the new president, Manuel Urrutia, a quiet judge who had joined the rebel army, and on the other by Archbishop Enrique Pérez Serantez, the priest who had baptized him and whose efforts had gotten him freed from prison. That same day Che Guevara and Camilio Cienfuegos entered Havana and took control. In grand style, Castro chose a symbolic march toward Havana at the head of the victorious rebel army. The march took five days, and he used every opportunity to showcase in front of the masses. He started in the back of a jeep, wearing his olive-green uniform with his precious M-2 rifle with its telescopic sight slung across his shoulder and a cigar clenched between his teeth. Before he entered Havana, he was riding on the back of a captured military tank, and nine-year-old Fidelito joined him for the final entrance.

The victorious rebel army, numbering only 7,250 fighters, had defeated Batista’s 46,000 U.S.-armed troops. The transfer of power was surprisingly orderly. Castro had warned his soldiers against looting and destruction of property. When several caches of arms were found to have been stolen, Castro, worried about the possibility of a separate seizure of power, used his next speech to ask, “Arms for what purpose?” Afterward, the Student Directorate, who had taken the arms, sheepishly returned them.

Castro’s base of power lay in his blindly loyal rebel army, most of whom were illiterate peasants. He realized that he would need the help of educated people to actually run the country. He chose José Miró Cardona, one of his former professors, to be prime minister; Roberto Agramonte, chairman of the Orthodox Party, to be foreign minister; and Manuel Urrutia, to be president. Castro himself was content to be supreme commander of the armed forces, while keeping his closest allies in the background.

Behind the scenes, Castro began to lay the foundation of a parallel system of power, in which he held complete control. Under the name “Bureau for Revolutionary Planning and Coordination,” Fidel brought together many of his old friends from the movement, including Raúl Castro, Che Guevara, Camilio Cienfuegos, and Alfredo Guevara. The group met regularly at Castro’s headquarters, the top three floors of the Havana Libre Hotel (formerly the Havana Hilton). Castro was known as the Máximo Líder (Maximum Leader).

In the weeks after the revolution, some 550 Batista “criminals” were court-martialed and summarily executed. The worst incident occurred in Santiago de Cuba, where seventy prisoners were killed by rebel soldiers at the command of Raúl Castro and then dumped in a mass grave. Three of Batista’s most notorious thugs were put on public trial in the athletic stadium in Havana. The angry crowd chanted “Parédon!”, meaning “Up against the wall.” By the end of the year there had been about 1,900 executions.

In May 1959, Castro instituted a program of agrarian reform, nationalizing foreign holdings on the island, especially those of the U.S. sugar producers. He also created the National Agrarian Reform Institute (INRA), which gave structure to his hidden government. Soon INRA was responsible for nearly all decisions, including the building of infrastructure. INRA was supported by the reconsolidated military, the Revolutionary Armed Forces, under the control of Raúl Castro.

IF YOU DON’T SUPPORT ME, YOU ARE THE ENEMY—With the INRA, backed by the Revolutionary Army, making the political decisions, there was little need for the puppet government. By July, Castro had decided that he no longer needed President Urrutia. On July 16, Castro announced his resignation, saying that he could no longer work with the president and accusing him of betrayal. Castro then disappeared for several days. As planned, the Cuban population responded with massive protests and calls for Urrutia’s removal. Humiliated and fearing for his safety, Urrutia disguised himself as a milkman and took refuge in the Venezuelan embassy before going into exile. Ten days later, Castro was back in power. He cemented his control by placing his most loyal allies in key positions of power. Fidel put Raúl Castro in control of the military and made Che Guevara, despite his complete lack of any relevant economic experience, director of Cuba’s Central Bank.

Still, the purges continued. The next to go were former members of Castro’s own July 26 Movement. In October, Huber Matos, a former Sierra Madre fighter who was in charge of the economically important Camagüey province, sent Fidel Castro a letter of resignation. In it he expressed his concern with the direction of the government and his wish to return home. He did emphasize that he continued to support Castro and wished him success in the future. To Castro, however, anyone not wholly supportive of his regime was his enemy, and he ordered Matos’ arrest, as well as that of forty officers who shared his views. Although Raúl wanted Matos shot, Fidel settled with having him sentenced to twenty years in prison. Soon afterward, Camilio Cienfuegos died under suspicious circumstances. Cienfuegos, who was sympathetic to Matos, was on his way to Havana for a meeting with Castro when his Cessna 310 disappeared. No trace of the aircraft or its passengers was ever discovered.

Having removed all allies even remotely suspected of being disloyal, Fidel and Raúl turned their attention to external security. After taking power, they had incorporated many soldiers and officers from Batista’s army into the Revolutionary Armed Forces, which numbered approximately 100,000 by the beginning of 1960. Over the next twelve months, the army tripled in size. Additionally, the army was supported by hundreds of thousands of lightly armed militias, recruited from the general population. These militia members were expected to use guerrilla tactics to combat any attempted invasion.

With Castro’s blessing, interior minister Ramiro Valdés created a new secret police organization, the G-2, which was supported by the creation of the Committees for the Defense of the Revolution (CDRs), whose task it was to track down suspected saboteurs and traitors. Like Batista before him, Castro soon began to silence critical media, shutting down newspapers, radio stations, and television stations.

FINDING A PLACE IN THE COLD WAR—In April of 1959, less than six months after taking control of Cuba, Castro, in his first visit as head of state, traveled to the United States. He was welcomed with open arms, both by the American public and the Cuban exile population, and more than 30,000 people came to see his opening speech in New York’s Central Park. The U.S. government, on the other hand, played it cooler. President Dwight Eisenhower went on a golfing vacation, leaving Vice President Richard Nixon to meet with Castro. In fact, the CIA was already making plans for Castro’s removal, and the U.S. government applied pressure to block the international sale of arms to Cuba.

Back home, Castro made contact with the Soviet Union, and in February 1960, he signed an agreement to trade Cuban sugar for various Soviet products. In July, Raúl Castro traveled to the Soviet Union and reached an agreement with Nikita Khrushchev for a program of military aid. Nevertheless, the leadership of the USSR was wary of the Castro brothers and not yet convinced that it wanted Cuba as an ally.

Castro ordered the American-owned refineries in Cuba to process oil imports from the Soviets. When the companies refused, Castro nationalized their holdings. In response, Eisenhower cut 700,000 tons from the U.S. annual purchase commitment, in what Castro would describe as the American “Dagger Law,” designed to stab the revolution in the back. Castro countered by nationalizing all U.S.-owned agricultural and industrial firms on the island, and then all large commercial businesses still under private control. The American Mafia alone had to write off about $100 million of their holdings in the tourist industry. These nationalizations also created a huge expatriation of the Cuban middle class. Between 1960 and 1962, 200,000 highly educated citizens fled the island, mostly settling in Florida. These included doctors, engineers, technicians, economists and scientists.

BACK IN THE USA—In September 1960, Castro made his second trip to New York. He planned to speak at the United Nations and wanted to attract the world’s attention. When the eighty-three-person Cuban delegation arrived in New York, they claimed that their rooms at the Shelburne Hotel on Lexington Avenue were far too expensive, and that the hotel had asked for a deposit of $10,000. In dramatic style, Castro’s convoy gathered up their luggage, piled into cars and, followed by dozens of reporters, drove to the United Nations building. There, Castro confronted the secretar- general, Dag Hammarskjøld, and told him that they would either sleep in the UN building or in Central Park. Finally, the entire convoy set off for the seedy Hotel Theresa, in the middle of Harlem, where they settled in. It was here that Fidel received the leaders of the non-aligned movement, including Indian premier Jawaharlal Nehru and Egyptian premier Gamal Abdel Nasser, as well as Nikita Khrushchev, whom he welcomed with a big bear hug. In fact, the entire affair had been a publicity ploy. The Cubans had been offered a steeply discounted room rate of only $20 per day at the Shelburne Hotel and wound up paying more for their rooms at the Hotel Theresa. When Castro had stormed out of the Shelburne, he had even been offered free rooms at the Commodore Hotel near the UN building. At the UN General Assembly meeting, Castro spoke for four and a half hours, until even his allies were on the verge of falling asleep.

THE BAY OF PIGS INVASION—By March of 1960, relations between Cuba and the United States had become so strained that President Eisenhower gave the green light for the organization and training of a group of Cuban exiles to invade the island. On January 3, 1961, the United States officially broke diplomatic ties with Cuba. When John F. Kennedy replaced Dwight Eisenhower as president of the United States less than three weeks later, he inherited the planned invasion. At that point, the plot had already been reported in the New York Times, and Castro undoubtedly knew that something was afoot. The CIA and the State Department considered several landing sites for the invading forces and decided on the Bahía de Cochinos, or Bay of Pigs. The bay covered a thirty-mile long stretch of coast, in an isolated and swampy region.

Prior to the invasion, on April 15, the United States made a surprise attack on the Cuban air force in an attempt to disable Castro’s planes. Castro had already hidden many of his aircraft, and although he lost five planes in the air strikes, in the end he still had more airplanes than pilots: eight planes and only seven pilots. After the air raids, Castro ordered the mass arrests of anyone suspected of being involved in an invasion force. By the time the invaders landed, between 100,000 and 250,000 people had been thrown in prison, scuttling chances for a larger popular revolt.

On April 17, Invasion Brigade 2506, escorted by American destroyers, reached the southern coast of Cuba. The force, which had left from Nicaragua three days earlier, numbered 1,511 men, all of them Cuban exiles. As they pulled out of the port at Puerto Cabezas, the Nicaraguan dictator Luis Somoza told them, “Bring me a couple of hairs from Castro’s beard!” The troops landed at dawn at Girón and Larga beaches, but had great difficulty slogging through the swamp to the shore. Many of their small boats got stuck in the reefs, and when the men waded ashore their walkie-talkies became wet, cutting off communication.

Within minutes, word of the landing had reached Castro. He sent his few remaining planes to attack the American support fleet. The Americans were so confident that they had destroyed the Cuban air force that they did not even put anti-aircraft guns in place for defense. By 6:30 a.m., the Cuban planes had scuttled the largest ship, the Houston, and had forced a second ship, the Barbara, back out to sea, leaving the invading force completely unsupported. At the same time, there were 25,000 Cuban troops and more than 200,000 armed militia in the area. Within sixty-five hours, after heavy losses on the Cuban side, the battle ended when the invading force ran out of ammunition. A total of 114 exile fighters had been killed, and 1,189 were captured. The rest escaped into the swamp or disappeared into the Cuban population. The captured men included many of Batista’s former henchmen. Five were executed, and the rest were eventually traded back to the United States in exchange for medical supplies worth $53 million. The attempted invasion of Cuba had failed spectacularly. Dozens of trials were held in front of revolutionary tribunals, resulting in nine executions.

THE NEXT CRISIS—In 1961, Castro announced the creation of the Integrated Revolutionary Organizations (ORI), which would eventually become the Communist Party of Cuba (PCC). At the same time, his regime began cracking down on anyone suspected of disloyalty to the revolution. Artists, poets, and intellectuals were the first targets. Catholics, Protestants and members of the Santería cult were also thrown into labor camps. Male and female prostitutes were jailed, as were homosexuals, who had to wear prison uniforms with a large letter “P” on their back, for “pimpillo” or pretty boy.

On December 1, 1961, on national television and radio, Fidel declared “I am a Marxist-Leninist and I shall be a Marxist-Leninist until the day I die.” The Soviet leaders in Moscow, however, were still dubious about taking responsibility for Cuba’s national defense. In their traditional New Year’s message to their friends and allies, they wished Castro, “success in the creation of a new society,” but made no mention of his statement. Almost a month passed before they even acknowledged it. On the American side, however, the response was immediate. The State Department moved to bring charges against Cuba in the Organization of American States and called for a meeting of foreign ministers to discuss Castro’s removal. In February 1962, the U.S. government imposed a total economic blockade of Cuba, causing the loss of some $600 million in foreign currency earnings. The following month, Castro was forced to place restrictions on basic products. Rations were imposed, and Cubans were given a small book of coupons which were supposed to guarantee them access to a fair share of food and other products. Castro blamed the shortages on the U.S. embargo and the move pushed Cuba even closer to Moscow.

In May, the Politburo in the USSR decided to offer Castro the stationing of Soviet missiles on the island. The original plan called for forty mobile ballistic missile launching pads, with a range of between 1,100 and 2,200 nautical miles. By mid-July, shipments of equipment and weapons began to arrive in Cuba. In October, the United States was finally alerted to the presence of missile sites on the island, and the Cuban Missile Crisis had begun. The first real evidence that Cuba had received missiles from the Soviets came on October 14, when Major Richard S. Heyser flew a U-2 spy plane over the San Cristobál area of Western Cuba and recorded photographic evidence of nuclear launch sites. For five days President Kennedy and his advisors struggled over whether to take preemptive military action, to blockade the island until weapons were withdrawn, or to reach a political deal with the Soviets. They reasoned that a military air strike might not guarantee the destruction of all missile sites and nuclear weapons, but it would almost certainly result in a Soviet response. Instead, Kennedy announced a military blockade around the island, which would be lifted only after all nuclear weapons had been withdrawn. He also announced that a military strike by Cuba on any country in the Western Hemisphere would be countered with a nuclear attack on the Soviet Union by the United States.

The crisis escalated, and all U.S. strategic missile units were placed on the highest level of alert, while 250,000 troops were put on standby for a possible military landing on Cuba. Castro sent a letter to Khrushchev urging the Soviets to launch a nuclear strike against the United States if it attempted to invade the island. Events reached a peak on the morning of October 27, when an American U-2A spy plane was shot down over Cuba by a Soviet ground-to-air missile, killing the pilot, Major Rudolf Anderson, Jr. Kennedy was urged to respond with force, but he resisted and the next morning Khrushchev officially announced that the missiles would be removed from Cuba in exchange for a U.S. agreement not to mount an invasion of Cuba nor support an invasion by a third party.

Castro was left out of the decision-making process. Neither Khrushchev nor Kennedy had consulted him, and in the end he only heard about the agreement through radio and newswire reports. From then on, although the Soviets would continue to offer significant economic aid to Cuba, their relationship would be little more than one of convenience. Khrushchev invited Castro to cover up his humiliation by making a forty-day trip through the Soviet Union. The gesture of reconciliation included assurances of generous amounts of economic aid. The U.S. government also took several steps to improve ties with Cuba. Back-channel communications were restarted between Havana and Washington, and Kennedy hinted at ending the economic embargo if Castro stopped supporting guerrilla groups in Latin America and distanced himself from the Soviets.

This warming of U.S.-Cuban relations was derailed, however, when Kennedy was assassinated in Dallas, Texas, on November 22, 1963. Castro was outraged when he heard about attempts being made to link him to the assassination.

COMPAÑERO CHE GUEVARA—Che Guevara, meanwhile, had grown into the ideological brains of the revolution. By 1963, however, Che’s socialist idealism had begun to conflict with Soviet economic plans for Cuba. The nation’s agricultural output fell by 23 percent, leaving a foreign trade deficit and lower living standards throughout Cuban society. The sugar harvest was the lowest since the end of World War II. As the regime’s industry minister, Che was held responsible and he openly criticized aspects of the regime, including its close ties to the Soviets. The following year, Castro signed a five-year agreement to sell Cuban sugar to the Soviet Union at a price above the world-market rate. In 1964, Castro agreed to remove Che from his ministry post and allow him to deal instead with foreign policy. Although he publicly denied having quarreled with Castro, Che began making long trips abroad to support foreign struggles for independence and armed revolutions, spending less and less time in Cuba. He traveled to Algeria, after which Castro agreed to send a battalion of Cuban soldiers and tanks to help the Algerian government in its armed conflict with Morocco. Previously, he had given Cuban military aid to the Algerian National Liberation Front in its struggle against France. Che visited various areas in Africa where colonial struggles were taking place, including Angola, Mozambique, Guinea-Bissau, Mali, the Congo, Senegal, Ghana, Tanzania, and Egypt. While in Algiers, Che gave a speech criticizing the Soviet Union’s economic practices and calling for an end to Cuba’s trade agreements with the Soviets.

When Che returned to Cuba on March 15, 1965, he was brought before Fidel and Raúl, and during their closed-door meeting the friendship among the three finally ended. Che left Cuba on April 2, without saying goodbye to Fidel, and set off for the Congo. There he joined a group of guerrilla fighters around Laurent Kabila, who would eventually become that nation’s dictator. Che continued to travel, reaching Bolivia in November 1966. Within a year, he had been tracked down by Bolivian officers and soldiers, and was eventually killed by Bolivian soldiers trained by Green Berets and the CIA.

SUGAR FANTASIES—Meanwhile, back in Cuba, Castro had announced sweeping changes to the agrarian system, embarking on what would be a series of agricultural fiascos. The Cuban trade deficit with the USSR had mushroomed to $4 billion, so Castro tried to increase agricultural production. His first plan revolved around the sugar harvest, and he announced a target of 5.5 million tons for 1965, increasing to 7 million tons and eventually reaching 10 million tons by 1970. Castro called 1970 “the year of the ten million tons,” but from the beginning, more realistic observers doubted whether the target could be achieved. Castro poured all of Cuba’s energy into the sugar cane harvest, leaving almost all other economic activity at a standstill. Virtually the entire Cuban population was put to work cutting cane, including mothers, children, pensioners, white-collar workers, and the military. Even visiting foreign dignitaries were asked to cut cane, and Castro himself cut for four hours almost every day. Christmas was abolished for 1969, and growing cycles were changed to allow for more production. With so much effort going into cutting cane, the rest of the Cuban economy fell between 20 and 40 %. Worse yet, it soon became clear that the target was indeed impossible to achieve. In July 1970, Fidel was forced to announce that the ten million tons had been a failure. In his usual style, he made an impassioned plea to the people and announced his resignation. The Cuban population responded with their support and he quickly returned to power.

SUPERCOW—In the early 1960s, Castro became increasingly interested in the techniques and science of farming and animal husbandry. His ideas and schemes to improve Cuban agriculture abounded, and included a campaign to rid the island of all weeds, an idea to plant a circle of coffee plants in a huge ring around the island, and a plan to produce a Cuban Camembert that would rival that of Normandy. In 1964, he invited a noted French agronomist, André Voisin, to make a lecture tour of Cuba. Castro had been impressed by Voisin’s book, Grass Productivity. When Voisin arrived, Castro arranged an exuberant series of dinners, social events, lectures, and sightseeing tours. Evidently the strain of celebrity was too much for Voison because, on December 21, after three weeks of being feted, Voisin suffered a heart attack and died while visiting a state farm. Undaunted, Castro continued to look for ways to improve the Cuban agricultural industry, this time in dairy production.

Prior to the revolution, Cuba had had a population of cattle in the millions, mostly the indigenous Cebú variety. The cattle were well-adapted to the tropical climate, but were notoriously poor producers of milk. American Holsteins, by contrast, languished during the dry season but produced far more milk. Fidel ordered the purchase of several thousand of the most expensive Holsteins from Canada. Within the first few weeks, nearly one-third died in the intense Cuban heat. Castro then ordered the construction of special air-conditioned dairy farms, a move that might have benefited André Voisin had Castro thought of it earlier. Castro next announced a plan to cross-breed the Cebú cattle with the imported Holsteins. The resulting F-1 hybrid, he claimed, would inherit the vigor of the tropical cows with the productive capacity of the purebreds. Ignoring the protests of animal husbandry experts and breeders, Castro poured resources and propaganda into the project. One cow, named Ubra Blanca, or White Udder, became so famous that after her death Castro ordered her stuffed and placed in a museum. Unfortunately, the project was a complete failure. Even fifteen years later, the resulting F-1s were still producing less than half the milk of the average American Holstein.

TRYING TO GAIN INTERNATIONAL RESPECTABILITY—Although he was the ruler of a small country, Fidel Castro had dreams of glory. By the end of the 1970s he was providing aid to thirty-five Third-World countries. Part of this outreach had to do with medical training and health care, a legitimate specialty of Castro’s Cuba. Even today, Cuba has a lower infant mortality rate and a higher life expectancy than the United States. However, Castro also wasted a lot of his nation’s limited resources in support of dubious military ventures, including the bloody civil war in Angola and a war between Ethiopia and Somalia. In September 1979, Castro’s international efforts reached their peak when Havana played host to the Sixth Non-Aligned Conference, which made Castro its official spokesman for the next four years.

FLEEING THE SOCIALIST PARADISE—In 1965 the United States declared its willingness to accept any Cubans who sought asylum. Over the next six years, so many Cubans chose to flee the country that there were fears that almost one in every five Cubans would emigrate. The loss of income and of skilled labor, the “brain drain,” was considerable, and Castro finally forbade the flights. Between 1959 and 1980, a total of 800,000 people are estimated to have left the island. This exodus came to a head on April 1, 1980, when a bus crashed through the front gates of the Peruvian embassy in Havana, killing a guard. The six people inside the vehicle asked for political asylum. Outraged, Castro made a tactical error, removing all protection from the embassy. When the news spread that no one would be prevented from entering or leaving the grounds, Cubans flooded into the compound. Within five days, 10,000 people had descended upon the embassy, occupying nearly every square inch. When the Peruvian government refused to accept the refugees, Costa Rican President Rodrigo Carazo offered to allow the Cubans to go to his country. Castro responded by announcing that anyone in the embassy grounds could go home, pack their bags, and leave for wherever they wanted. The next day hundreds of boats packed with families from all over the country left Cuba. By September, when Castro reintroduced travel restrictions, an estimated 125,000 people had fled the country, many headed for the United States. Photographs and video of the massive exodus were shown around the world, delivering a blow to Castro’s image of Cuba as a socialist paradise. It is estimated that between the 1959 revolution and the year 2000, 10 to 15 percent of the Cuban population fled the country, with a majority of them settling in Florida.

SUGAR RUSH—In the early 1980s, sugar prices and harvests were so good that the Cuban economy was growing at a rate of 24 %, while Latin America as a whole declined by 9 %. Then a worldwide slump in sugar prices drove Cuba’s debt to the West from $2.8 billion in 1983 to $6 billion in 1987. Even worse, the Cuban debt to the Eastern bloc rose to almost $19 billion. The Soviet Union tried to save Castro’s Cuba by increasing trade between the two countries. In 1989 the Communist governments in Eastern Europe fell apart and all economic agreements with them became worthless. To make matters worse, in the early 1990s, a series of hurricanes swept across Cuba, decreasing sugar production even more and causing almost $1 billion in damage.

The struggling economy meant that military spending had to be scaled back, and restrictions placed on food and household supplies. Milk was available only for children and those with special needs, and soap, detergent, toilet paper, and matches became precious commodities. Cooking oil and flour were distributed only on a limited basis, as were fruit, jam, and butter. Every two years citizens were entitled to buy four pairs of underwear or bras, two pairs of socks, one shirt or blouse, and four meters of material to make trousers or dresses. At the same time, the black market shot up, from $2 billion to $14.5 billion in less than four years. Energy consumption was slashed by fifty percent, and electricity became sporadic throughout the country. Tractors were replaced with ox carts, and people began to wait two to three hours for infrequent city buses.

Faced with an economy on the verge of collapse, in 1993 Castro gave permission for Cubans to start private businesses, mostly in the service sector. He also allowed them to own and spend U.S. dollars. In September 1994, he reestablished farmers’ markets. The following year, he enacted a law that permitted foreign investors to own Cuban businesses in almost every area of the economy, a right that had previously been limited to the tourist industry. Cuba’s economic output, which had declined 40% between 1989 and 1994, stabilized and began to grow.

In 1995, U.S. president Bill Clinton attempted to counter this trend by signing into law the Helms-Burton Act, a strengthening of the thirty-five-year-old embargo against Cuba that included a ban on any loan or financial assistance to the island; a ban on the import from a third country of any products that contained materials processed in Cuba; and a stipulation that the embargo could only be lifted once a transition government was in power in Cuba that moved toward a market-oriented economic system and that did not include either Fidel or Raúl Castro. The act also required the return of all property seized by the rebels from U.S. citizens.

The biggest beneficiary of Castro’s economic reforms has been the military, which is run by his brother Raúl. The Ministry of Armed Forces manages GAESA (Grupo de Adminstración de Empresarial), a huge conglomerate of businesses involved in tourism, mining, consulting, construction and international trade, and is thought to employ at least 20% of Cuban workers.

CATHOLICISM AND COMMUNISM— Since the early days of his revolution, Castro had had difficulty with the Catholic Church. In 1962, Pope Pius XII excommunicated Castro after his announcement that he was a Marxist-Leninist. From that point on, Castro restricted and persecuted the church and its followers. Much of its property was confiscated and many members of the clergy were expelled from the country. Castro officially proclaimed Cuba an atheist country. He finally became more tolerant of religion in 1992, allowing religious Cubans to join the Communist Party. In 1998, Pope John Paul II was invited to tour Cuba and give large public masses. The pope spoke out against the human rights abuses within the country, but encouraged greater cooperation and reconciliation between the church and Cuba. That same year Castro approved nineteen visas for foreign priests to take up residence in the country. He also allowed Cubans to celebrate Christmas as a holiday for the first time since the 1960s.

THE OVER-THE-HILL DICTATOR—The 1990s found Fidel an aging, lonely dictator. He had quit smoking his trademark cigars in 1985, as part of an anti-smoking campaign on the island. Most of his close allies had been either killed or exiled. He kept up his practice of not sleeping in the same place more that two nights in a row, and he now traveled in a column of three bullet-proof Mercedes limousines with a heavily armed guard.

By 1999, the Cuban National Assembly approved a series of measures that increased penalties for crimes, including a death penalty for drug-related crimes and longer prison sentences for robbery with violence. Sentences of up to twenty years were threatened against anyone providing information to the U.S. government or any foreign enemy or collaborating by any means with foreign media for the purpose of destabilizing the socialist state. At the time, an estimated 110,000 people, roughly one percent of the population, was serving time in prison or labor camps. Of these, at least 3,000 were presumed to be political prisoners. According to a 2005 report by Amnesty International, “the Cuban authorities continue to suppress any form of dissent by methods such as harassment, threats, intimidation, detention and long-term imprisonment.”

THE REVOLUTION DEVOURS ITS CHILDREN—At the same time that Cuba was rising to power in the international sphere, Castro was imposing more restrictions on domestic liberties. In 1971, in response to the arrest of Cuban poet Heberto Padilla, an open letter was published in the French paper Le Monde, criticizing the repressive system in Cuba. The signatories included authors of both the left and the right, including Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Mario Vargas Llosa, Carlos Fuentes, Susan Sontag, and Gabriel García Márquez. In 1989, one of the most celebrated “Heroes of the Revolution” was brought down: Arnaldo Ochoa Sánchez, a general in the Cuban army and a veteran of the Sierra Maestra, the Bay of Pigs, and guerrilla campaigns in Venezuela, the Congo, Ethiopia, Angola, and Nicaragua. The popular Ochoa had become a magnet for disaffected army officers and veterans, who gathered at his house in increasing numbers. Sensing a threat, Castro ordered Ochoa and three other high-ranking officers arrested for drug smuggling. The trial was a sham, and it received worldwide attention when all four were given death sentences, despite the fact that the maximum sentence for drug smuggling was twenty years in jail. Ochoa maintained his innocence, and his allegiance to the regime, until his execution by firing squad. He was buried in an unmarked grave. With Ochoa’s execution, Castro sent a strong message to the increasingly disillusioned military that he would tolerate no dissent within the armed forces or society in general.

In March 2003, Castro took advantage of the world’s preoccupation with the U.S. invasion of Iraq to crack down again on political activists and dissidents. Cuban police arrested seventy-eight journalists, political students, and independent librarians and charged them with conspiring to overthrow the government. Most were sentenced, in closed-door trials, to between fifteen and twenty-eight years in prison. Over the next year, fourteen of the dissidents were released, but the majority have remained in prison. In response to the arrests, Cuban activist Oswaldo Paya delivered a petition to the Cuban National Assembly with more than 14,000 signatures, demanding a referendum to change the Cuban political system and protect civil liberties. It was the second year that Paya had delivered the petition. When he did so in 2002, with more than 11,000 signatures, Castro responded by conducting his own referendum, winning an overwhelming majority (98.97% of the vote according to the Cuban government) to amend the constitution and declare socialism on the island “irrevocable.”

CIA PLOTS—Marita Lorenz, Fidel Castro’s former translator and lover, was recruited by the CIA in a plot to kill Castro using a pill made from shellfish toxin. At the last moment, however, she could not bring herself to go through with the plan, and instead flushed the pill down the toilet. Two years later, a barman by the name of Santos de la Caridad was hired to slip a botulism pill into Castro’s milkshake during his weekly visit to the bar. The plan was foiled, however, when the pills stuck to the inside of the freezer and shattered as they were being removed. Santos was too nervous to pick up the pieces of the pills and put them into the drink. Other CIA assassination ideas included a plan to give Castro a box of poisoned cigars, a plan to coat the inside of his diving suit with tuberculosis bacteria, and a plan involving a rifle disguised as a television camera. The CIA even devised a plan to slip Castro a substance that would make his beard fall out, thus humiliating him and causing him to lose the respect of the Cuban people.

THE NUMBER 26—Castro remains superstitious about certain dates and numbers. He attaches great importance to the number 26, having been born in 1926, on April 13 (which is half of 26) and having started his conspiracy against Batista in 1952, at the age of twenty-six. The attack on the military base in Moncada, for which Castro chose the date, took place on July 26, 1953, and his revolutionary movement took the name The 26th of July Movement. Castro frequently chooses the twenty-sixthday of the month to deliver key speeches or to make major decisions, such as March 26, 1962, when he spoke out against the so-called Sectarians of the Communist Party, who were challenging his rule. Of course, all this good luck would be ruined if he acknowledged that, as his sisters claim, he was really born in 1927.

-David Wallechinsky

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments