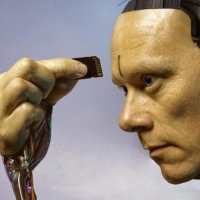

Americans Wary of Future Science Designed to “Enhance” Human Species

(photo: Peter Sherrard via Getty Images)

(photo: Peter Sherrard via Getty Images)

By Gina Kolata, New York Times

Americans aren’t very enthusiastic about using science to enhance the human species. Instead, many find it rather creepy.

A new survey by the Pew Research Center shows a profound distrust of scientists, a suspicion about claims of progress and a real discomfort with the idea of meddling with human abilities. The survey also opens a window into the public’s views on what it means to be a human being and what values are important.

Pew asked about three techniques that might emerge in the future but that are not even close to ready now: using gene editing to protect babies from disease, implanting chips in the brain to improve people’s ability to think, and transfusing synthetic blood that would enhance performance by increasing speed, strength and endurance.

The public was unenthusiastic on all counts, even about protecting babies from disease. Most, at least seven out of 10, thought scientists would rush to offer each of the technologies before they had adequately tested or even understood them.

Two-thirds say they would not want the enhancement technologies for themselves. And even though genetic manipulations appear more frightening than a chip or artificial blood, which might be removed, the public finds it slightly more acceptable to change a baby’s genes than to enhance human abilities.

Religiosity affected attitudes on these issues. The more religious people said they were, the less likely they were to want genetic alterations of babies or technologies to enhance adults. The differences were especially pronounced between evangelical Protestants and people who said they were atheists or agnostics.

For example, 63 percent of evangelical Protestants said gene editing to protect babies from serious diseases was meddling with nature. In contrast, 81 percent of atheists and 80 percent of agnostics said it was not fundamentally different from other ways humans have tried to better themselves.

Cary Funk, an associate director at Pew and lead researcher for the survey, said she was surprised by the extent of the public’s worries. “These are appealing ideas: being healthier, improved minds, improved bodies,” she said. And she was surprised that the public seemed nearly equally worried about all three of the technologies. After all, she said, “these are three different kinds of technologies, for different purposes.”

The survey queried a nationally representative sample of 4,700 adults, supplemented by discussions with six focus groups.

Much of the concern about enhancement reflects worries about doing something that seems unnatural, a worry that shows up in many contexts. For example, it is legal for athletes to sleep in low-oxygen altitude tents to develop more red blood cells, which enhance performance.

But it is not legal for them to use the hormone EPO to achieve the same effect. And it ties in to distrust of scientists and corporations trying to sell a product. It is the sort of distrust that is reflected in the controversy over genetically modified organisms. For years scientists and companies have insisted that foods containing GMOs are safe, but many people do not believe them. In another recent Pew survey, 88 percent of scientists said it was safe to eat these foods, but only 37 percent of the general public thought it was.

In a way, the public’s wariness about science and its uses is part of a long history of worries about new technologies. The cautionary tales go back beyond Frankenstein’s monster and continue into the present. When in vitro fertilization was developed, many were vehemently opposed to it, fearing it would result in damaged babies. There was a flurry of concern about genetic engineering, with fears about using it to alter humans — and there were even greater concerns when cloning was developed.

The three specific technologies noted in the Pew survey are recent advances. Gene editing has been taken up by thousands of laboratories around the world with the recent discovery of a method that allows researchers to home in on a gene of interest and delete, replace or alter it. The method, known as CRISPR, is still under development — it can lead to the unintended alteration of other genes — and no one is ready to start altering genes of babies.

Even if CRISPR were perfected, there are other problems with gene editing to prevent disease. For example, how and when would you alter these genes? And what diseases are you thinking of eliminating? Most involve many genes acting together in ways that are not understood, so even the idea of altering a gene to protect a baby from disease seems, for now, to be limited to a very few disorders, like sickle cell, which involves a single mutation that can be corrected in blood cells that are easily accessible.

The idea for synthetic blood came from a report out of Britain last year that scientists were planning to start giving synthetic blood as a substitute for donated human blood. There was no thought of making people stronger or faster. But if synthetic blood could, for example, carry more oxygen, the possibility of enhancement exists. Once again, though, it is a futuristic notion.

This year, researchers reported they had put a chip in the brain of a quadriplegic man that transmitted signals to a sleeve around his arm, allowing him to use it. Of course, that is a far cry from implanting brain chips to make people smarter or better able to concentrate, something that scientists do not know how to do.

Conversations in focus groups reflected the trends in the survey, with people saying they worried about what is natural and about the risks of altering humans. Nearly half said it would be acceptable to use synthetic blood, for example, if it simply restored a person’s peak abilities. But more than three-quarters were opposed to using it to make people faster or stronger than would otherwise have been possible.

For example, a 35-year-old man in an Atlanta focus group said, “You would have this culture of people just obsessed with being bigger, stronger, faster, and just outperforming everybody.”

A 27-year-old woman in the Boston area said of brain chips: “The thing just keeps going over in my brain is that you’re altering the brain. It’s such a high risk.

“When you think about DNA, OK, but it’s your brain. It’s so complex and I just feel this is very, very high risk.”

The public was also concerned about equity, worried about creating a society of enhanced versus unenhanced humans. A 50-year-old woman in Phoenix said: “Who gets the promotion at work? Because you could afford to have an implant, so you get it? I mean, what about everybody else?”

There may be lessons here for scientists and corporations as they develop technologies that could make people healthier or enhance their abilities. But, as the struggles over GMOs illustrate, knowing the public is leery does not necessarily help scientists know how or even whether to assuage their fears.

To Learn More:

Key Findings on How Americans View New Technologies that Could ‘Enhance’ Human Abilities (by Brian Kennedy and Cary Funk, Pew Research Center)

Chinese Scientists Cause Alarm after Announcing Editing of Human Genes (by Noel Brinkerhoff, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments