Supreme Court Supports Companies Forcing Arbitration as Alternative to Class Action Suits

(graphic: Lapin Law Offices)

(graphic: Lapin Law Offices)

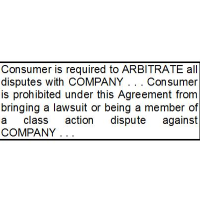

In the coming year, millions of American consumers will unknowingly suffer a serious loss of their constitutional rights, simply by receiving a billing statement from a creditor or service provider. Thanks to a Supreme Court case decided last week, the “Terms and Conditions” documents included with a bill—and invariably set in tiny print—will contain obscure legal language that strips away the constitutional right to demand a jury trial if a dispute arises.

The case—American Express v. Italian Colors—arose when numerous retail shops, led by a California restaurant called Italian Colors, filed a class action antitrust suit against American Express (2012 revenues: $33.8 billion) alleging that AmEx refuses to allow retailers to accept its charge card unless they also agree to accept its credit card, which carries merchant rates about 30% higher than competitors like Visa or MasterCard. Contending that this scheme constitutes an illegal tying arrangement, the merchants alleged that American Express used its monopoly power to force them to accept the credit cards, costing them about $40,000 each.

But the standard contract imposed by American Express requires that disputes be handled through individual arbitration, by an arbitrator chosen by AmEx. Relying on the doctrine of “effective vindication,” the merchants argued that because handling the legally complex cases individually would cost up to $1 million each, individual arbitration could not provide “effective vindication” of their claims.

In an under-reported but potentially historic decision last week, a sharply divided U.S. Supreme Court voted 5-3 to reject the retailers’ argument, ruling that large corporations may force contractors—and potentially consumers and employees—to waive their constitutional right to a jury trial in favor of private arbitration decided by a firm of the corporation’s choice. Justice Sonia Sotomayor did not participate in the case because she was on the appeals court panel whose decision was appealed by Amex to the Supreme Court.

Sweeping away the effective vindication doctrine, Justice Antonin Scalia wrote that “the antitrust laws do not guarantee an affordable procedural path to the vindication of every claim,” as though the substantive purpose of antitrust laws—or any other laws for that matter—is unaffected if enforcement is impossible. “The fact that it is not worth the expense involved in proving a statutory remedy does not constitute the elimination of the right to pursue that remedy,” he claimed.

Writing for herself and Justices Stephen Breyer and Ruth Bader Ginsburg, Justice Elena Kagan pointed out how easy the Court’s Republican majority has made it for corporations to simply declare themselves above the law:

If the arbitration clause is enforceable, Amex has insulated itself from antitrust liability—even if it has in fact violated the law. The monopolist gets to use its monopoly power to insist on a contract effectively depriving its victims of all legal recourse. As a result, Amex’s contract will succeed in depriving Italian Colors of any effective opportunity to challenge monopolistic conduct allegedly in violation of the Sherman Act.…In the hands of today’s majority, arbitration threatens to become…a mechanism easily made to block the vindication of meritorious federal claims and insulate wrongdoers from liability.

Although the AmEx case concerned an arbitration clause that limited class-action rights, Justice Scalia deliberately wrote the opinion broadly, emphasizing that the courts should “vigorously enforce” arbitration clauses. Given that principle, and the fact that there is nothing in the majority opinion to suggest that the case is limited to class-actions or even to suits between business entities, it is most likely that the Court intends the AmEx case to apply broadly. Unless the case is overturned by the Court itself or reversed by Congressional statute, virtually all constitutional and statutory rights, including rights to be free from discrimination, could be viewed as “waivable” under arbitration clauses forced on consumers and employees by large corporations.

-Matt Bewig

To Learn More:

Worst Supreme Court Arbitration Decision Ever (by Paul Bland, Public Justice)

Supreme Court Sides with American Express on Arbitration (by Robert Barnes, Washington Post)

Justices Support Corporate Arbitration (by Binyamin Appelbaum, New York Times)

American Express v. Italian Colors (Supreme Court, 2013) (pdf)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments