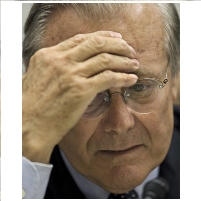

Rumsfeld and Torture: The Walls Close In

Wednesday, December 17, 2008

The Senate Armed Services Committee has issued a devastating report that concludes that the use of torture at Abu Ghraib prison and other sites was not the work of isolated “bad apples,” but the direct result of directives issued by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Before going into the details, it is worth noting who signed off on the Senate report. The 13 Democratic members of the Armed Services Committee and the 12 Republican members of the Committee voted unanimously to approve the report. Among the Republicans who agreed with the conclusions were John McCain and arch-conservatives John Cornyn of Texas and Saxby Chambliss of Georgia. Among the Democrats: Hilary Clinton, Joe Lieberman and Edward Kennedy. If ever there was a Senate report that crossed party and ideological lines, this is it.

To understand how the Bush administration transformed the international image of the United States from a model of respect for human rights to a nation of vicious torturers, one needs to begin with the SERE training program. SERE (survival, evasion, resistance and escape) training, most of which takes place at Fairfield Air Force Base in Washington, prepares aircrew members and “high risk of capture personnel” to survive under any conditions, including how to resist abusive interrogation techniques used by countries and terrorist groups that do not respect the Geneva Conventions for the treatment of prisoners of war.

On February 7, 2002, President George W. Bush signed a written directive that the Geneva Conventions did not apply to al Qaeda or Taliban detainees. This position was rejected by the U.S. Supreme Court on June 29, 2006, in the case of Hamdan v. Rumsfeld. In the meantime, however, Bush’s directive gave permission to U.S. interrogators to use the very techniques some of them had been trained to resist.

Over a period of several months, cabinet members, the National Security Council and senior administration lawyers discussed the use of various previously forbidden interrogation techniques, including forced nudity, stress positions, sleep deprivation and waterboarding. During the war crimes tribunals that followed World War II, a Japanese officer, Yukio Asano, was sentenced to 15 years hard labor for waterboarding a U.S. civilian. During the Vietnam War, in 1968, a U.S. soldier was court martialed for overseeing the waterboarding of a captured North Vietnamese soldier, and the technique was banned by the U.S. military.

However, in 2002, after consultations with Alberto Gonzales, Counsel to President Bush, and David Addington, Counsel to Vice-President Cheney, the Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) concluded (incorrectly, in the judgment of the Supreme Court) that U.S. anti-torture laws did not apply to President Bush’s Global War on Terrorism. According to the Senate Armed Services Committee report, the OLC opinions “distorted the meaning and intent of anti-torture laws” and influenced Department of Defense decisions as to which interrogation techniques were legal.

On December 2, 2002, Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld signed an “action memo” authorizing the use of dogs, forced nudity, stress positions and 20-hour interrogations at the Guantánamo Bay prison. Rumsfeld rescinded the authorization six weeks later, but on April 16, 2003, he approved techniques to be used at Guantánamo. These techniques then “migrated” to Afghanistan and Iraq.

In addition to Rumsfeld, Bush, Cheney, Gonzales and Addington, the Senate report points the finger of moral, if not legal, guilt at several other officials. These include:

Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff General Richard Myers and his Legal Counsel, Captain Jane Dalton, for conducting “a grossly deficient review…at odds with conclusions previously reached by the Army, Air Force, Marine Corps, and Criminal Investigative Task Force.” Myers also “undermined the military’s review process” by cutting short the legal review.

Major General Geoffrey Miller for ignoring warnings from the Department of Defense’s Criminal Investigative Task Force and the FBI that “techniques were potentially unlawful and that their use would strengthen detainee resistance.” Miller personally encouraged interrogators in Iraq to be more aggressive.

Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez for “serious error in judgment” in issuing a September 14, 2003, directive regarding interrogation techniques despite his knowledge that there were ongoing discussions regarding the legality of the techniques.

Department of Defense General Counsel William J. Haynes II, who “undermined the military’s review process” by cutting short the legal review. The report called “deeply troubling” his reliance on a legal memo produced by Guantánamo Staff Judge Advocate Diane Beaver that senior military lawyers had deemed “legally insufficient” and “woefully inadequate.” Haynes’ directive to consider OLC lawyer John Yoo’s legal memo authorizing abusive techniques as authoritative blocked “a fair and complete legal analysis” and contained “profound mistakes in legal analysis.” Reliance on this memo led to the use of techniques SERE trainees are taught to resist, including sleep deprivation, forced nudity and slapping.

Joint Personnel Recovery Agency Commander Colonel Randy Moulton for “serious failure in judgment” for authorizing SERE instructors with no interrogation experience to participate in interrogations in Iraq.

Guantánamo Staff Judge Advocate Lieutenant Colonel Diane Beaver for conducting a legal review that was “profoundly in error and legally insufficient.”

Office of Legal Counsel (AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Orders ICE and Border Patrol to Kill More Protestors

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

Comments