Texas Courts Accused of Criminalizing Poverty with Debtors’ Prisons

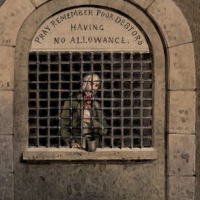

Debtors' prison depicted in early 19th-century graphic (Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, Wikimedia)

Debtors' prison depicted in early 19th-century graphic (Thomas Hosmer Shepherd, Wikimedia)

By Harvey Rice, New York Times

GALVESTON - It was only a traffic ticket, but it plunged Dee Arellano into a five-year cycle of seemingly endless debt.

Fees were tacked on to fees, and the courts never exercised the power to lower them for her or offer available alternatives, such as community service or an indigent waiver program.

"There is no out, honestly, there is no way out," the 36-year-old single mother from Houston said. "Even if you want to do the right thing, you want to pay your citation, you get caught up in this spider web of citations that are tangled up with late fees and surcharges and there is no transparency or an institutional way out."

Arelleno is among thousands of Texans living in poverty who have found themselves ensnared in a legal system that brings increasing debt and often lands them in jail because they are unable to pay traffic fines, according to a new report (pdf) by the American Civil Liberties Union.

The ACLU is working nationwide to end the jailing of poor individuals for unpaid fines, said Nusrat Choudhury, senior staff attorney at the civil rights group's Washington office.

"In 2015 alone, the ACLU brought lawsuits to challenge debtors' prisons in four states and exposed the practice in three others," said Choudhury, adding that they are "spanning the country."

'Criminalizing poverty'

The Texas report found "a pattern of local courts criminalizing poverty, and perpetuating racial injustice, through unconstitutional enforcement of low-level offenses."

Arellano, for example, was moving from one low-paying job to another in 2011, often leaving them when work conflicted with care for her son. Forced to choose between buying groceries and making auto insurance payments, she chose the former and was ticketed for lacking insurance. She paid the $250 fine, not realizing that her traffic debts would multiply. She eventually paid $1,200 in surcharges to the Department of Public Safety.

Although one in seven Texans lives below the poverty line - that's $12,000 a year for an individual, $19,000 for a couple with a child - they face excessive court fines and often are thrown into jail without notice or a chance to argue their case, the report says.

The practice is unconstitutional and amounts to a debtors' prison, the report alleges.

Courts also tack dozens of fees on to tickets, turning traffic enforcement into a revenue source that victimizes the poor in order to fill city coffers, according to the report.

Remedies for Texas offered by the report include judges asking about the ability to pay before sentencing; an end to financing public services with fees tacked onto traffic fines, which are assessed disproportionately against the poor; less reliance on traffic fees for city budgets; and a notice to defendants about their rights and sentencing alternatives,

The report also recommends hearings before an arrest warrant is issued; ending the suspension of drivers' licenses and of registration renewal for failure to pay; expanding programs for waiving surcharges; and legislation to tighten the existing ban on jailing people for inability to pay a traffic fine.

The report covers every municipal court in Texas disposing of more than 100 cases per year and focuses on the Houston area because it has been a source of so many complaints, said Tirisha Trigilio, a staff attorney with the ACLU of Texas.

"We took a really deep dive into a lot of courts in the Houston area," Trigilio said.

After analyzing statistics from the Texas Office of Court Administration on 766 municipal courts in Texas, the report singled out those in Houston, Galveston, Texas City, League City, Conroe and Stafford, among others.

Justices of the peace are engaging in the same questionable practices, Trigilio said, but they could not be included in the report because they do not offer data to the state agency.

Santa Fe sued

Although it was not included in the report, the city of Santa Fe in Galveston County was found to be the worst offender in the Houston area when it comes to jailing the poor for traffic debt, Trigilio said.

The ACLU filed suit this month against Santa Fe on behalf of three men, accusing the city of "running a modern-day debtors' prison, prioritizing raising revenue for the city over administering justice fairly." The lawsuit names the city, Municipal Judge Carlton Getty and Police Chief Jeffrey Powell.

William Helfand, an attorney representing Santa Fe, declined to comment on specific allegations in the lawsuit.

"People can put all kinds of accusations into a lawsuit, many of which do not bear out," Helfand said. "Most of the time in a lawsuit, many allegations turn out to be completely false."

Trigilio declined to make available for comment the plaintiffs in the lawsuit, But the lawsuit offered the following account of the alleged treatment of one plaintiff, 28-year-old Brady Fuller of Santa Fe.

Fuller, who supports a wife and three daughters, lives near the poverty line of $28,440 a year for a family of five. He was jailed twice for unpaid traffic fines even though he informed officials about his inability to pay. He voluntarily entered jail the first time after being told he had to pay or go to jail. The second time, a state trooper allegedly yanked him from a company vehicle he was driving, with his boss sitting in the passenger's seat, and turned him over to a city marshal, who took him to jail.

Fuller was never advised of his right to counsel and the city marshal threatened to revoke a security permit necessary for his job, according to the lawsuit.

The lawsuit accuses police of starving Fuller by serving a pop tart for breakfast and lunch and a frozen dinner in the evening, a 720-calorie daily intake that is less than the 1,000 calories needed by a 1-year-old child.

The report says that judges are forbidden from jailing anyone for a criminal conviction unless they are represented by an attorney.

"But our local courts simply don't follow the law," the report says. "People who are jailed for failure to pay their fines are almost universally too poor to pay."

The report singles out Houston, Texas City and League City as running debtors' prisons. Houston is accused of jailing people on Christmas Eve and Christmas Day for failing to pay traffic fines.

In an emailed response to questions, Houston Municipal Courts spokeswoman Gwendolyn Goins did not challenge any of the ACLU's specific allegations. "The City of Houston Municipal Courts have been operating under a collection of rules and practices promulgated by the Texas State Office of Court Administration and state law," Goins said.

Texas City was accused of racial disparity, with blacks making up 59 percent of those jailed for debt in a city with a 29 percent black population. Texas City municipal court officials did not respond to numerous requests for comment.

Questions of accuracy

League City issued a statement: "We're concerned there are some inaccuracies with the data ACLU listed in their recent report. Our municipal court complies with all laws relating to criminal prosecution, and our judges regularly work with indigent defendants to resolve their fines and court costs without jail commitment." The statement did not detail the alleged inaccuracies.

Poor defendants get thrown into debt the moment they enter the courthouse, the report alleges. Judges routinely ignore the ability to pay a traffic fine, according to the report, imposing penalties from a list of 25 authorized fees that go as high as $750. Additional fees vary from a $3 court charge to a $40 penalty that goes to 14 state funds.

Judges can reduce fines to as low as $1 but cannot waive court costs and fees until after a failure to pay puts the violator in danger of jail, the report says.

Caught in 'bureaucratic maze'

"A person who cannot afford her traffic-ticket debt is put into a bureaucratic maze that virtually guarantees that she will receive even more tickets," the report says. If they are late on their payments, they can be prohibited from renewing their car registration. The fines also make it impossible to pay for insurance, causing the loss of coverage. Needing to drive to get to work or take their children to school or to the doctor, they get more tickets and the debt piles higher.

If they are late on a payment, the state Department of Public Safety automatically adds a $250 surcharge.

"Because of these offenses resulting from poverty, it is not uncommon for someone with a low income to accrue $1,000 or more in traffic tickets in a short period of time," the report says.

Many cities view traffic citations as a source of revenue, with some assigning operation of the municipal court to the finance department.

The report alleges that the "reliance distorts the legitimate purpose of local courts - administering justice - and encourages court officials to view their mission as maximizing collection of revenue."

The ACLU took the Galveston municipal court to task for calling its report to City Council a "production report." Galveston Municipal Court officials did not respond to requests for comment.

States and cities nationwide are recognizing the problem and taking action, ACLU attorney Choudhury said. Ohio and Michigan have taken measures to ensure that judges check for the ability to pay before issuing arrest warrants, and the city of Biloxi, Miss., has created a public defender's office to represent the poor when they are faced with an arrest warrant.

No such office exists in Waller County, where a 28-year-old African-American woman, Sandra Bland, committed suicide in the county jail in 2015 after she was unable to post the $500 needed for bail. She was jailed after a routine traffic stop escalated into a heated exchange with a state trooper, who has since been indicted for perjury.

Waller County commissioners did not act on requests that the county establish a public defender office, with the county judge there saying recently that the county was "nowhere close to being large enough to justify that type of expense."

To Learn More:

No Exit, Texas: Modern-Day Debtors’ Prisons and the Poverty Trap (ACLU of Texas) (pdf)

Debtor’s Prison Charges Leveled at Austin, Texas (by Noel Brinkerhoff and Steve Straehley, AllGov)

Debtors’ Prisons may be Illegal, but they still Exist in Texas and Washington (by Noel Brinkerhoff, AllGov)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Renames National Football League National Trump League

- Trump to Stop Deportations If…

- Trump Denounces World Series

- What If China Invaded the United States?

- Donald Trump Has a Mental Health Problem and It Has a Name

Comments