A Visit to North Korea (In Disguise)

Monday, December 19, 2011

Having written about dictators for many years, I thought I would try to visit North Korea, the worst of the worst. Because I had written harshly about Kim Jong-il, and included a chapter about him in my book Tyrants: The World's 20 Worst Living Dictators, it was difficult for me to obtain a visa. But I was able to come up with a successful ruse. This is an account of that trip in 2007.

In the center of Pyongyang, the capital of North Korea, a huge bronze statue looms above the city. It portrays Kim Il-sung, the late father of the country’s current dictator, Kim Jong-il. Kim Il-sung is known in North Korea as “The Great Leader” and “The President for Eternity.” I watched as groups of schoolchildren placed flowers in front of the statue and then, in unison, bowed their heads in reverence. As I turned to leave, I heard an odd sound. Behind the statue was a man whose job it was to prevent birds from defecating on The Great Leader’s image by jumping up and down and waving his arms while yelling, “Whoosh.”

For the past five years, I had written an annual article for Parade about the worst dictators currently in power. Every year, Kim Jong-il earned the first or second spot on my list. I decided the time had come for me to visit North Korea and see the world’s most repressive regime for myself. It is difficult for journalists and professional photographers to gain a visa to North Korea. Because the Internet is not available in North Korea, when I applied for a visa as the vice president of the International Society of Olympic Historians (which I am), no one seemed to notice the other side of my career.

I travelled to North Korea with my sons, Elijah (24) and Aaron (22) and three friends. There were seven other people on our tour, all of whom turned out to be, like me, journalists or photographers in disguise.

Often when I go to isolated countries I bring with copies of my book, The Complete Book of the Summer Olympics, to present to each country’s National Olympic Committee. I soon learned this was not possible in North Korea. Our tour organizer had me autograph two copies not to Olympic officials, but to “The Dear Leader” (Kim Jong-il). She arranged for the books to be packed in silk-lined boxes. When we arrived at the airport in Shenyang, China, on our way to Pyongyang, officials of Air Koryo, the North Korean airline, were informed that I was bringing a gift for The Dear Leader. When we boarded the plane, my sons and I were given a row of three seats. In front of us were three Koreans. Flight officers bumped the Koreans from their seats and put my gift copies to The Dear Leader in their place.

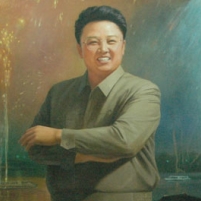

Kim Jong-il has developed the world’s most advanced personality cult, a fact that I noticed the minute that we landed. Not only does a large portrait of Kim Il-sung sit on top of the airport terminal, but every single person in the airport and on the streets was wearing a lapel pin with the smiling face of The Great Leader. Images of father and son are everywhere: on billboards, in every subway car, in every classroom and library, in every home. My sons and I practiced smiling like Kim Jong-il, but it’s not easy.

For at least three generations, North Koreans have grown up being taught that Kim Il-sung is responsible for inventing the philosophy they live by (known as Juche), the farming methods they use and everything else that shapes their lives. North Korea even uses its own calendar, measuring time from the year of Kim Il-sung’s birth (1912). Thus our 2008 is North Korea’s “Juche 97.” Even the most popular flowers are named the Kimilsungia and the Kimjongilia.

Throughout our five-day stay in North Korea, our group was accompanied everywhere and at all times whenever we left our hotel (which was on an island) by three guide/minders, two men in their late twenties and early thirties and an 18-year-old guide intern who had just graduated high school. The intern’s plumpness in a nation of thin citizens was an indication that she came from an elite family. Our guides were likable and seemingly intelligent, which made it all the more bizarre when they shared some of their beliefs.

I told one of our guides that I had heard that Kim Jong-il was a fan of the movies. The guide was indignant. “No,” he exclaimed. “He is not a fan; he is a genius of cinema.”

I asked if it was true that Kim Jong-il had designed the uniforms for the “traffic girls” who direct Pyongyang’s sparse traffic. Our guide replied, “Of course!”, as if I had just asked the dumbest question in the world.

One guide told us that although soccer is the most popular sport in North Korea, he personally preferred basketball because “Kim Jong-il has taught us that Koreans are a short race, and playing basketball will make us taller.” (According to James T. Morris, executive director of the UN’s World Food Program, in North Korea 7-year-old boys are almost 8 inches shorter than South Koreans of the same age.)

A Pyongyang “Traffic Girl” ordering phantom cars to halt during midday rush hour.

In North Korea-Speak, Kim Jong-il does not “visit” farms, factories and studios, or even “inspect” them. Rather, he provides “on-the-spot guidance.” At the national library we were told that Kim Jong-il had provided on-the-spot guidance 7 times, but at the national film studio he had done so 550 times. However, the last time was in 1998. What could have distracted The Dear Leader from his love of cinema? My sons and I looked at each other and had the same thought…the Internet. Sure enough, a week later, Kim Jong-il bragged to the president of South Korea that he was “an Internet expert.”

The Dear Leader providing on-the-spot guidance during the filming of the North Korean epic Sea of Blood.

One night, one of the guides unintentionally summed up North Korean life more succinctly than I ever could. “We have many rules and regulations,” he warned us, “and it is very important to follow them…although we don’t always know why.”

I have travelled to many countries with repressive governments, including China when everyone dressed in blue, Burma, Vietnam, and Spain under Franco, but this was the first in which I was not allowed to walk on the streets or talk with the local people. On my last day in Pyongyang, our minders allowed us to stand on a sidewalk for 20 minutes. One surprised toddler, to the embarrassment of his grandmother, shaped his hand into a gun and pointed it at my face. On the other hand, an elderly gentleman walked right up to my son, Aaron, looked him up and down, and gave him a big smile.

The only reason we were allowed to enter North Korea was to contribute foreign currency by attending the Arirang Mass Games. (We had to pay cash in Euros for our tickets.) The participants, numbering in the tens of thousands, far exceeded the number of spectators, almost all of whom were North Koreans. Of course it is a shocking display of mass psychology, but honestly, as a spectacle, it was much more impressive than the many Olympic Opening Ceremonies I have covered, and it made the Super Bowl halftime show look like amateur hour. Here we see, as usual, The Great Leader, this time formed by thousands of young people performing card stunts.

At the Mass Games, several of my male companions were particularly taken by the comely North Korean women dressed in military uniforms with short skirts and wielding swords.

North Korea is the most isolated country in the world. Cell phones are illegal—mine was confiscated upon arrival at Pyongyang Airport and returned when I left the country. The Internet is not available to normal citizens, and newspapers and television provide nothing but government propaganda. All home radios and televisions are set to government channels, and security forces enter people’s homes to make sure no one has tampered with the dials. The North Korean people have no clue as to what really goes on beyond their borders. According to Selig Harrison, director of the Center for International Policy’s Asia program, “Unlike Eastern Europe, where TV, short-wave radios and cassettes leapfrogged national boundaries, North Korea has been tightly insulated from outside influences.”

North Korean development is hampered by major problems, such as the perceived need to support a huge army, and by widespread poverty. Kim Jong-il’s mismanagement of the economy and his initial refusal to accept foreign aid, led to a famine between 1994 and 1998 that resulted in hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of deaths.

We were repeatedly told that all of the nation’s problems were caused by the United States. At the Demilitarized Zone that separates North Korea from South Korea, a soldier-guide told us that the reason U.S. troops are stationed in South Korea is to prevent the two nations from reuniting. We were also taken to see the USS Pueblo, the US spy ship that was captured by North Koreans in 1968. One crew member was killed and 82 tortured and held captive for 11 months. Although this incident is almost forgotten in the United States, North Korea still celebrates it as a major victory. We were supposed to be impressed by this great achievement, but really the North Koreans were acting like a little guy who once decked the champ with a lucky punch and still tries to live off the story 40 years later.

For the last 15 years, the Pyongyang landscape has been dominated by an enormous unfinished pyramid-hotel with a crane on top. Construction began in 1987 and was halted in 1992. It looks like the Leaning Tower of Pyongyang. Despite all of Kim Jong-il’s propaganda, for me this eyesore is the real symbol of the North Korean system. It is too poorly built to finish, and Kim Jong-il believes he will lose face if it is demolished. I tried to explain to one of our guides that it looked bad. I suggested that they cover up the unfinished floors with large portraits of The Great Leader and The Dear Leader. He burst into uncontrolled laughter. I don’t know why.

The North Korean authorities have thoughtfully constructed overhead bridges to allow pedestrians to cross the streets without interfering with traffic. Of course, there is no traffic, but at least the citizens of Pyongyang are able to build their muscles by climbing up and down.

It always seemed as if every part of our visit was staged. For example, when we visited the Grand People’s Study Hall, we were shown a room in which one young man was working at a laptop computer. My son, Elijah, walked closer to take a photo, and discovered that the “student” was robotically switching back and forth between two screens, one of which was a blank document. We even wondered if the cars that we saw on the streets of Pyongyang, few as they were, were being driven in front of us repeatedly to make it appear that traffic was heavier than it is. Whenever we went on an outing, the bus driver would take us on the same streets, where the apartment buildings looked clean and electric lights shined through curtains. But between the buildings we could glimpse more ramshackle neighborhoods. Even the soldiers drove around in jeeps and trucks that appeared to be at least 15 years old. Yet I knew that for North Koreans it is a privilege to be allowed to live in Pyongyang, and that what we were being shown was the best the country had to offer.

Once, though, the show fell apart. Midway through our two-hour drive to the International Friendship Exhibition, which displays gifts given to Kim Il-sung and Kim Jong-il, our bus broke down. Our guides tried to flag down one of the infrequent cars that passed, but anyone in a car in North Korea is too important to stop to help. The bus driver actually asked us if we had chewing gum to help him try to repair the gas tank.

After a long wait, we continued for a few more miles before breaking down again. This time we stopped beside a platoon of soldiers. We were ordered by our guides not only to stay on the bus and not take photographs, but to not even take notes. In any other country, the guides would have used their cell phones to call their office and ask for a replacement bus. But in North Korea cell phones are illegal. After much haggling, one of our guides convinced the soldiers to loan him a bicycle, upon which he raced north towards the nearest hotel, five miles away. Eventually he returned with a bus he had borrowed from a group of Chinese tourists who were eating lunch. Unfortunately, this bus, too, broke down, and we were forced to walk the rest of the way to the hotel. As we trudged up the final hill, I was struck by the seeming absurdity that this nation that could not even transport a group of tourists to an intended destination could somehow propel a nuclear weapon several thousand miles towards the United States or convey its army across the Pacific Ocean to launch a land invasion of California. We never did make it to the International Friendship Exhibition.

I was well aware of the North Korea we were not allowed to see. The entire population is divided into “loyalty groups” based on a family’s social and economic status in the year 1945. Below these classes are the 250,000 North Koreans whom Kim Jong-il condemns to prison camps. Following the concept of “family purge” (yongoje), if a citizen is accused of a crime, three generations of his family are also either imprisoned or banished to remote areas.

What we did get to see of the countryside was quite beautiful. However, our guides told us that we were not allowed to photograph it. Puzzled, I asked why. “Normally, it is alright to take photos of the countryside,” explained our guide, “but because the president of South Korea is coming for a visit next week, this week photos are not allowed.” Oh.

As hostile as is the government of Kim Jong-il, I can’t help but look at the North Korean people themselves as victims rather than enemies. If ever there was a population that has been brainwashed by its leaders, it is the North Koreans. They have absolutely no access to information or opinions that are not fed to them by Kim Jong-il’s propaganda machine.

The night before we entered North Korea, we had dinner at a North Korean restaurant in China. My sons met an executive of a North Korean company that develops surveillance and recognition technology for the Chinese. After a pleasant conversation about computers, the North Korean executive told my sons, “You don’t seem like Americans.” My sons asked him how many other Americans he had met. “None. You’re the first.” All it took was one encounter with real Americans for this North Korean to realize that Americans are not the bloodthirsty demons he had been taught we are.

It is difficult to deal with the challenge of overthrowing dictators because different dictatorships require different tactics. Sudan and Burma, for example, are worth boycotting. In the case of North Korea, however, the country is so poor that there isn’t much to boycott, and an invasion would be a disastrous waste of lives. North Korea’s isolation is so extreme that the first step needs to be to expose its citizens to what is really happening in the rest of the world so that they become aware of alternatives to the propaganda fed to them by their government.

-David Wallechinsky

(Photos by Elijah Wallechinsky)

- Top Stories

- Unusual News

- Where is the Money Going?

- Controversies

- U.S. and the World

- Appointments and Resignations

- Latest News

- Trump Goes on Renaming Frenzy

- Trump Deports JD Vance and His Wife

- Trump Offers to Return Alaska to Russia

- Musk and Trump Fire Members of Congress

- Trump Calls for Violent Street Demonstrations Against Himself

Comments