Over-Pumping of Groundwater Is Sinking the San Joaquin Valley Fast

(graphic: Lawrence Lessig)

(graphic: Lawrence Lessig)

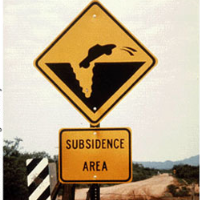

The San Joaquin Valley is sinking.

That, of course, is not a good thing for what it tells us about the rapidly declining groundwater infrastructure beneath it. But the sinking also bodes ill for the California Aqueduct and the Delta-Mendota Canal, which pass through it, carting fresh water around the state, according to a new study from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS).

“We were surprised at the amount of land being affected,” Michelle Sneed, a USGS hydrologist and the report's lead author, told the Sacramento Bee. “We were also surprised by the rapid rate of (sinking).”

Sinking land in the valley is not new. California has been pumping water out of the ground there for over a century. Land subsidence was first noted on the 10,000-square-mile valley floor in 1935. The amount of sinking varies depending on the site and the amount of pumping taking place, but one location, in Mendota, showed a 28-foot drop between 1925 and 1977.

More than 80% of the subsidence in the United States is caused by exploitation of groundwater sources. The surrounding rock compacts and the resulting displacement wreaks havoc with above-ground structures and terrain. Subsidence is a global problem, and an estimated 17,000 square miles in 45 states—the size of New Hampshire and Vermont, combined—are impacted by it.

The Central Valley, which includes the San Joaquin Valley, the Sacramento Valley and the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, produce 25% of the nation’s table food. Groundwater pumping for agricultural irrigation, starting in the 1920s, caused major disruptions in land contours.

Subsidence slowed when completion of the canal in 1951 and the aqueduct in the 1970s provided alternative sources of water to the area, but the USGS study indicates there is still a significant problem that continues to get worse.

Increased pumping during drought years of 1976-77, 1987-92 and 2007-10, when shipments of imported water from the north declined, reduced groundwater levels and speeded up subsidence. In 2008, subsidence rates doubled in some areas and the sinking continued unabated through 2012, according to the USGS report.

The sinking has been hard on the Delta-Mendota Canal and the California Aqueduct, which is, itself, a system of canals, tunnels and pipelines. Canals were built with slopes to help propel the water, taking advantage of existing geography. When that geography changes quickly, it can disrupt canals, drainage ditches, associated bridges and pipes, and other infrastructure.

And it has done just that in the valley. The study found sinkage of 1 foot per year in some areas, slowing the flow of water through the key canals.

The effect of subsidence on the canals isn’t the only concern. Anything that passes along the surface of the valley is at risk if sinking continues. It could be more than just a bump in the road for the high-speed rail project just getting up a head of steam. A rapidly evolving landscape could also damage roads, pipelines and railways.

California has not had a good track record of late at getting big infrastructure projects in gear. The bullet train is stalled, the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta makeover is mired in controversy and government technology projects crash and burn with frustrating regularity.

When viewing the prospects of mitigating subsidence in the San Joaquin Valley, it’s hard not to avoid a distinct sinking feeling.

–Ken Broder

To Learn More:

USGS Finds Land Sinking Rapidly in Central Valley (by Jason Dearen, Associated Press)

Land Subsidence Along the Delta-Mendota Canal in the Northern Part of the San Joaquin Valley, California, 2003-10 (by Michelle Sneed, Justin Brandt, and Mike Solt, U.S. Geological Survey) (pdf)

- Top Stories

- Controversies

- Where is the Money Going?

- California and the Nation

- Appointments and Resignations

- Unusual News

- Latest News

- California Forbids U.S. Immigration Agents from Pretending to be Police

- California Lawmakers Urged to Strip “Self-Dealing” Tax Board of Its Duties

- Big Oil’s Grip on California

- Santa Cruz Police See Homeland Security Betrayal in Use of Gang Roundup as Cover for Immigration Raid

- Oil Companies Face Deadline to Stop Polluting California Groundwater