8 Days on the Road with the Oakland Police License Plate Readers

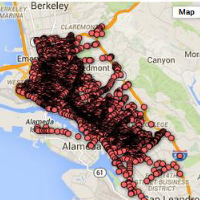

Places where license plates were snapped (graphic: Electronic Frontier Foundation)

Places where license plates were snapped (graphic: Electronic Frontier Foundation)

Last September, Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge James Chalfant rejected the request of advocacy groups to look at one-week’s worth of data gathered by LAPD using automated license plate readers (ALPR). He ruled that keeping cop operations secret was more important than the public’s right to privacy.

One of the groups, the Electronic Frontier Foundation (EFF), was more successful in Oakland, where the city acceded to its California Public Records Act requests for data on the readers and crime stats during the same period. EFF crunched the raw data and punched out some numbers, charts and a video, “Eight Days in the Life of Oakland’s Roving Automatic License Plate Readers.”

Oakland only has two cop cars equipped with cameras that drive around town taking pictures of vehicles driven by people who are not suspected of having done anything wrong. A lot of cities and counties use a lot more. A vehicle’s plate number, GPS location, date, time and possibly a picture of the occupants is stored in a computer.

Two cars managed to take 63,272 pictures, capturing 48,717 unique individual plates. They overwhelmingly took pictures in lower-income neighborhoods, so the end result was, not unsurprisingly, low surveillance of the white population. “Overlaying Census data for African-American and Latino populations shows the converse of the white population,” EFF said.

If, in focusing on neighborhoods of color, police expected to be deterring crime, it didn’t seem to work. EFF found that police “did not use ALPR surveillance in the southeast part of Oakland nearly as much as in the north, west, and central parts of Oakland, even though there seems to be just as much crime.” Surveillance also did not correlate well with areas experiencing automobile-related crimes.

EFF picked a week in Ramadan for its data request because it wanted to see if mosques received any special attention. The data set was small, but there did not appear to be a special focus in their vicinity. EFF and others are interested to see if any special attention is accorded gun shops, bars, public gatherings, political events, medical marijuana dispensaries, abortion clinics and protests.

While Oakland’s ALPR effort is limited, others are not.

ALPR are deployed by police departments and state agencies in dozens of states. The LAPD has 242-car mounted cameras and 32 at fixed locations snapping away at up to 60 plates a second, according to Ars Technica. Around 28 jurisdictions in L.A County use plate readers.

This is big data, that is growing exponentially across the country. Instant, available data on the vehicular movements of everyone, across time, is not beyond reach. But it’s only one small piece of a larger surveillance network.

Last March, the Oakland City Council was poised to expand the Homeland Security-funded Domain Awareness Center beyond the port and airport to the entire city. They were looking for data streams—from schools, the Coliseum, law enforcement agencies, license plate readers, digital license plates, private security cameras, news feeds, red-light cameras, the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans) and other sources.

After a public outcry, the council voted 5-4 not to expand the system.

–Ken Broder

To Learn More:

What You Can Learn from Oakland's Raw ALPR Data (by Jeremy Gillula and Dave Maass, Electronic Frontier Foundation)

If You Drive In Oakland, Police Probably Know Where You’ve Been (by Nicole Jones, CBS Bay Area)

You Are Being Tracked: How License Plate Readers Are Being Used to Record Americans' Movements (American Civil Liberties Union)

Judge Lets LAPD Hide License Plate Reader Data from Public (by Ken Broder, AllGov California)

Oakland Backtracks on Expanding Port Surveillance Center to Entire City (by Ken Broder, AllGov California)

- Top Stories

- Controversies

- Where is the Money Going?

- California and the Nation

- Appointments and Resignations

- Unusual News

- Latest News

- California Forbids U.S. Immigration Agents from Pretending to be Police

- California Lawmakers Urged to Strip “Self-Dealing” Tax Board of Its Duties

- Big Oil’s Grip on California

- Santa Cruz Police See Homeland Security Betrayal in Use of Gang Roundup as Cover for Immigration Raid

- Oil Companies Face Deadline to Stop Polluting California Groundwater